New York State.

This was not the case in Brooklyn or Kings County, NY, a slaveholding capital. Following the American Revolution, slavery actually strengthened in Kings County, unlike neighboring Manhattan, Philadelphia, and Boston. Enslaved labor was essential to the county’s growing agricultural economy and prosperity.

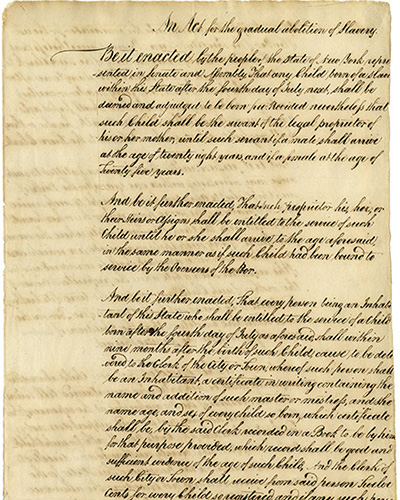

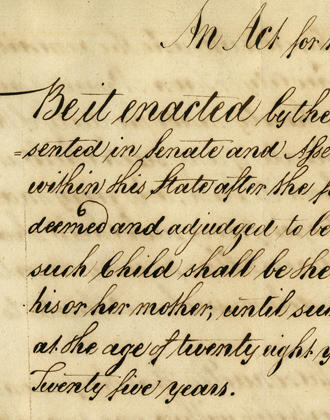

Finally, in 1799, New York State enacted a Gradual Emancipation Act. It was the second to last Northern state to begin the dismantling of slavery. The law stated that all children born to enslaved mothers after July 4, 1799 would be free at the age of 28 if male, and 25 if female. Slavery had no end date for those born prior to 1799. In 1817, a further act stipulated that slavery would come to an absolute end on July 4, 1827.

Gradual emancipation lasted 28 years and there was no guarantee of equality at its end. But as long as slavery existed so did the desire to be free and enslaved people found ways to resist their oppression. They were assisted by a small, but significant, free black community who resided in the town of Brooklyn. These pioneers represented the first wave of anti-slavery activists.

Slaveholding Capital

Section 1: Lesson 2

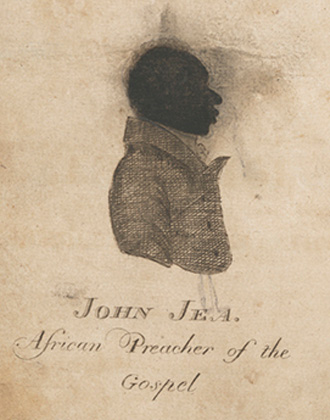

The horses usually rested about five hours a day, while we were at work; thus did the beasts enjoy greater privileges than we did. (John Jea, The Life, History, and Unparalleled Sufferings of John Jea, 1811)

John Jea lived and worked in Flatbush, Kings County during the colonial period and in the early days of the American republic. He was just one of the thousands of enslaved people who fueled the prosperity of Kings County’s agricultural economy.

Jea was born in southern Nigeria in 1773. He was kidnapped at the age of 2½ and sold into slavery. Jea worked on a large farm in Flatbush. His slaveholders, Albert and Anetje Terhune treated him “in a manner almost too shocking to relate.”* The Terhunes forced their enslaved laborers to work eighteen hours a day, seven days a week, with a paucity of food and inadequate clothing. They beat, whipped, and even killed those who complained or could not work.

Read more...

* Jea states that his slaveholders were Oliver and Anjelika Treibuen in his autobiography. But historian Graham Hodges found no evidence of this couple living in Flatbush at that time. It is possible that Jea created these names to protect himself and others. According to Hodges his actual enslavers were likely to be Albert and Anetje Terhune.

As the reality of slavery of Brooklyn faded, the memories of the past – when they surfaced at all – tended to focus on the “mildness” of slavery in the North and the beauty of its agricultural backdrop.

Created in 1848, this image idealizes Cornelius Van Brunt’s former home in the late eighteenth century as a tranquil scene. The person of color works in a beautiful rural landscape. In 1796, a writer under the pseudonym “Amynto” stated that “in no part of the world do slaves live so comfortable as here [in New York].” But John Jea’s autobiography documenting his experience as an enslaved person showed that slavery was just as oppressive and dehumanizing in the North as it was in the South. Working on Kings County’s farms was often grueling and shortened the life expectancy of the enslaved.

Agricultural Brooklyn

By the late eighteenth century, Dutch and English colonizers had firmly established an agrarian economy in Kings County.

Read more...

During this period, Kings County remained distinctly agricultural, supplying fruit and vegetables to the county and neighboring New York.

Section 1: Lesson 1

Brooklyn was the slaveholding capital of New York State.

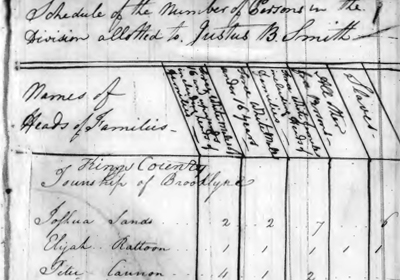

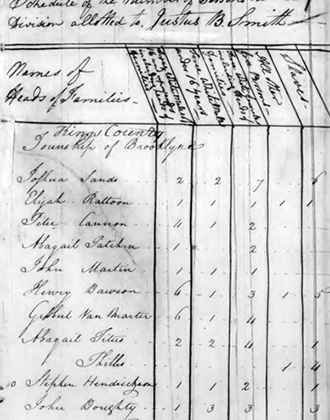

In 1790, the first official federal census revealed that the population of Kings County had doubled in less than a century. 4,495 residents, mostly of Dutch, English, and African descent, lived and worked on the county’s large farms.

Not all were free. In 1738, 25% of Kings County’s residents were held in slavery. In 1790, this number had risen to 30%. On average, 60% of white families were slaveholders; in outer areas, such as the town of Flatbush, this number was as high as 74%. Kings County was a slaveholding capital in New York State.

Slaveholding families that became wealthy during this period included the Lefferts, Lott, Bergen, Vanderveer and Vanderbeek families. Their names are still visible in Brooklyn’s landscape: the Prospect-Lefferts Gardens neighborhood and Lott Street in Flatbush; Bergen Street, which runs East-West from Cobble Hill to East New York; Vanderveer Street in Bushwick; and, Remsen Street (named after a descendant of Ram Jansen Vanderbeek) in Brooklyn Heights. In fact, 82 streets named after Brooklyn’s slaveholding families still exist in the borough today.

Gradual Emancipation

Section 1: Lesson 2

It took twenty-eight years for New York State, and therefore Kings County, to end slavery.

In 1799, New York State made provisions for the gradual emancipation of enslaved people. It was the second to last northern state to do so. After July 4, 1799 children born of enslaved mothers would be free at the age of 28 if male, and 25 if female.

Read more...

– the efforts of black people, both enslaved and indentured, to secure their own emancipation through running away, manumission and self-purchase,

– the legal mediation carried by an anti-slavery organization called the New-York Manumission Society,

– a grassroots campaign for equality initiated by Brooklyn’s free black community.

Their work was frequently met with hostility from Brooklyn’s landowners and farmers whose wealth was built on slavery.

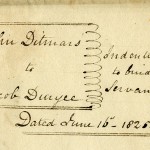

![[Slave bill of sale]. 1825. John Ditmars and Jacob Duryee slave bill of sale. 1977.583. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/013c_full.jpg)

Section 1: Lesson 4

Gradual emancipation laws favored slaveholders not the enslaved.

Sine, a young African American girl living in Brooklyn in 1825 was not legally enslaved. But her indenture to Jacob Duryee of Flatbush required that she work uncompensated from the age of eight to ten. Her service should have ended on July 4, 1827, when slavery was abolished in New York State. However, it is difficult to say whether Sine was ever emancipated. Outer areas such as Flatbush, Flatlands, Gravesend, and New Utrecht remained deeply agricultural until the late nineteenth century. Farmers in these areas continued to rely on the labor of African Americans who were held illegally in bondage and indentured servitude beyond 1827.

![[Slave bill of sale]. 1825. John Ditmars and Jacob Duryee slave bill of sale. 1977.583. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/013_crop.jpg)

![[Runaway advertisement for David Smith]. Long Island Star. January 10, 1822. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/014_full_alt.jpg)

Section 1: Lesson 4

Gradual emancipation in New York State (1799-1827) was a tumultuous period for people of color.

They demanded to live their lives with dignity and agitated for their own freedom. Running away, manumission and self-purchase were just three ways in which enslaved people secured their own emancipation.

In 1822, eleven-year old David Smith ran away from his enslaver in Brooklyn. Running away was a politically charged act of courage and revealed the ways in which enslaved people resisted their own bondage.

His slaveholder advertised David as a runaway in the local newspaper, the Long Island Star. “Runaway Ads” had been a prominent part of newspapers from the colonial period onwards in Kings County reflecting the economic worth of slavery in the region.

It is difficult to say whether David successfully built a new life as a free person or if he was captured and forced to serve his indenture.

![[Runaway advertisement for David Smith]. Long Island Star. January 10, 1822. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/014_crop.jpg)

Section 1: Lesson 5

By the terms of New York’s gradual emancipation act (1799) an enslaved person of color born before July 4, 1799 was condemned to a life in bondage. His or her contemporaries born after this date would be free at the age of 25 if female or 28 if male.

In 1817, New York State created a new law that would abolish slavery completely in 1827. During this uncertain period, there were three options for pursuing freedom: running away, manumission or self-purchase.

Read more...

Founded in 1785 by Manhattan’s white elite, the N-YMS was committed to gradually ending slavery. During gradual emancipation they focused on three primary concerns in Kings County: the enslavement of free African Americans; slave sales between New York and New Jersey; and, the violation of manumissions such as Harry’s. But many N-YMS members were slaveholders. The contradiction of being a slaveholding anti-slavery activist was not lost on the organization’s members. Rather, they felt that their reform work addressed their own sin of slaveholding and would eventually result in the economic collapse of slavery. Still, they remained unsure of the ability of African Americans to be their equals.

It is difficult to say whether Harry ever found his freedom.

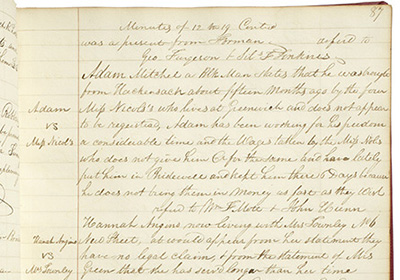

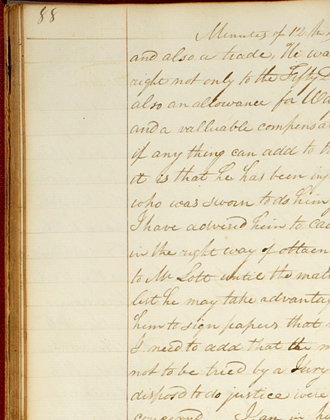

Section 1: Lesson 3

Margaret was a street crier who sold hot corn near the ferry on Fulton street during gradual emancipation (1799-1827)

Her enslaver was Robert Debevoise, a wealthy landowner in what is now Brooklyn Heights. Gabriel Furman, an early nineteenth century historian, lawyer and Brooklynite, reminisced that during his childhood “an old colored woman, familiarly known as Debevoise black peg, or rather, Margaret or Peggy, made her appearance, crying ‘Hot Corn, Nice Hot Corn, piping hot.’”

Margaret left no record of her own experiences, but Furman’s recollection confirms that countless oppressed women of color formed the social fabric of Brooklyn.

![[John Baxter house]. Harriet Stryker-Rodda. ca. 1945. Brooklyn photograph and illustration collection. V1973.5.2373. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/007_full.jpg)

Section 2: Lesson 2

Irish born John Baxter was a lifelong resident of Flatlands. Over three decades, beginning in 1790, he made copious notes in his journals. His entries reveal life during gradual emancipation had upon ordinary Brooklynites. Following are excerpts from his detailed journals:

June 30, 1790

A. Wyckoff purchased Harry, a black, Bett his wife, and Peg her child from Widow Lott for 180. I am afraid no great bargain.

August 12, 1807

Abraham Wyckoff’s negro ran off.

May 17, 1815

This morning my negro was to come home. I am afraid he had run away and we cannot account for it.

Read more...

My negro Will ran away.

June 10, 1815

Bought a negro Jack from J. Mead.

June 12, 1815

Negro jack who is free at 21 years or 28 according to law.

![[John Baxter house]. Harriet Stryker-Rodda. ca. 1945. Brooklyn photograph and illustration collection. V1973.5.2373. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/007_crop.jpg)

Early Free Black Community

Timothy Dwight, Travels in New England and New York, 1822.

Section 1: Lesson 6

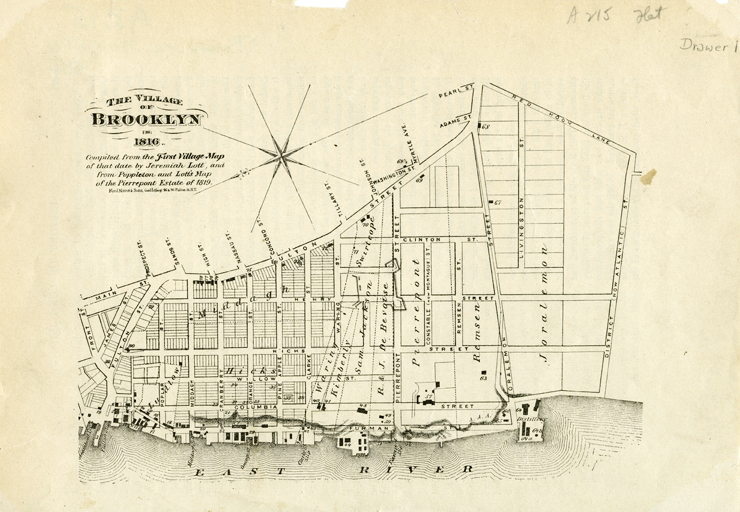

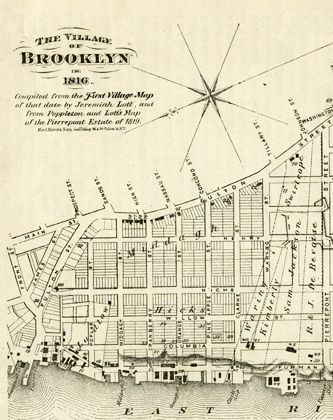

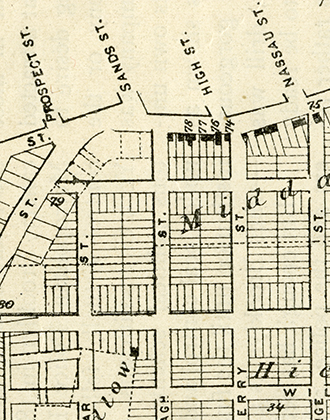

In 1816, the village of Brooklyn was incorporated within the town of the same name. Brooklyn had transformed from farmland to a bustling town centered around the ferry landing at the northwestern tip of Kings County.

Irish immigrants, transplants from New England, descendants of early English and Dutch settlers, and free African Americans lived side by side in its crooked streets.

Brooklyn’s free black community mostly lived among those of European descent in the neighborhoods we know now as DUMBO and Vinegar Hill, with the largest concentration in a triangle between Fulton, Main and Front Streets. Brothers Peter and Benjamin Croger, together with their growing families, were among the many residents.

Grassroots activists, the Crogers pioneered Brooklyn’s anti-slavery movement. Through assistance, education and faith they created an independent and strong community foundation, on which free black Brooklynites built lives of self-determination and dignity, despite significant oppression.

![[Cover of Constitution of the Brooklyn African Woolman Benevolent Society] adopted March 16, 1810, published in 1820 by E. Worthington. Negative #85470d. Collection of The New-York Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/019_full_alt.jpg)

Section 1: Lesson 6

A small, but significant, free black community lived in the areas now known as DUMBO and Vinegar Hill. They pioneered Brooklyn’s anti-slavery movement through grassroots efforts.

In 1810, Brooklynites Peter Croger, Benjamin Croger, and Joseph Smith established the Brooklyn African Woolman Benevolent Society. The mutual aid society’s name referred to noted Quaker anti-slavery activist John Woolman and reflected the organization’s anti-slavery commitment. The Society offered care and financial assistance especially to the widows and children of deceased members.

Read more...

![[Cover of Constitution of the Brooklyn African Woolman Benevolent Society] adopted March 16, 1810, published in 1820 by E. Worthington. Negative #85470d. Collection of The New-York Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/019_crop.jpg)

![[Advertisement for African School]. The Long Island Star. January 18, 1815. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/022_full.jpg)

Section 1: Lesson 6

The creation of a private African school symbolized literacy as a form of liberation.

In 1815, Peter Croger established a private African school at his home on James Street. The school offered day and evening classes in the “common branches of education.” Croger’s school was vital to the education of black Brooklynites after the district school refused to teach children of color.

Croger’s work symbolized literacy as a form of liberation. Through literacy, they sought to empower people of color to emancipate their minds from the mental oppression of racism. They also challenged the racist perception that people of African descent were not capable or prepared to be equal citizens in the United States.

![[Advertisement for African School]. The Long Island Star. January 18, 1815. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/022_crop.jpg)

Peter Croger’s private African school founded in 1815 was located on James Street.

Today the street no longer exists. It was demolished when construction on the Brooklyn Bridge began in 1870.

![[Bridge Street African Methodist Church]. Eugene L. Armbruster. 1923. Eugene L. Armbruster photographs and scrapbooks. V1974.1.1342. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/025_full.jpg)

Section 1: Lesson 6

Bridge Street AWME Church, Brooklyn’s oldest black church now located in Bedford-Stuyvesant, was founded by grassroots anti-slavery activists as a political base during gradual emancipation.

In 1816, Reverend Richard Allen founded the independent African Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia. Two years later, inspired by anti-racism developments in Philadelphia’s black community, Peter Croger, his brother Benjamin Croger, Israel Jemison, Cesar Springfield, and John E. Jackson founded the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church on High Street in Brooklyn.

Read more...

The Brooklyn AME Church became central to the lives of ordinary people. Not only a place of worship, it served as a venue for educational initiatives, political protests, and temperance meetings. They church also assisted with fugitives or freedom seekers newly arrived in the city.

![[Bridge Street African Methodist Church]. Eugene L. Armbruster. 1923. Eugene L. Armbruster photographs and scrapbooks. V1974.1.1342. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/025_crop.jpg)

Section 1: Lesson 6

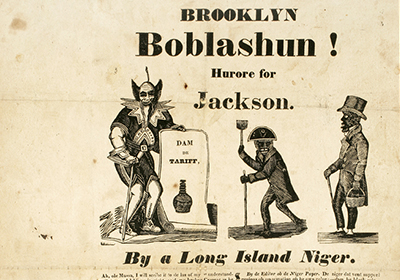

On July 4, 1827 slavery ended in New York State. Black New Yorkers chose to celebrate the next day in order to avoid reprisals and comment on the paradox of slavery and freedom in the United States.

Crowds gathered along Manhattan’s Broadway to celebrate Emancipation Day on July 5, 1827. James McCune Smith, a prominent abolitionist living in Manhattan, described it as a “real, full-souled, full-voiced shouting for joy … marching through the crowded streets, with feet jubilant to songs of freedom!” A week later, on July 12, 1827, black led benevolent societies took to the streets of the village of Brooklyn. They formed a “long and handsome procession,” accompanied by banners and several bands.

But emancipation brought tenuous liberties.

Read more...

During the post emancipation years, black Brooklynites confronted pervasive racial injustice. Inequality in education, housing, voting, and employment was commonplace. Despite their own oppression in “free” New York, communities of color strengthened their commitment to equality through self-determination, self-preservation and protest.