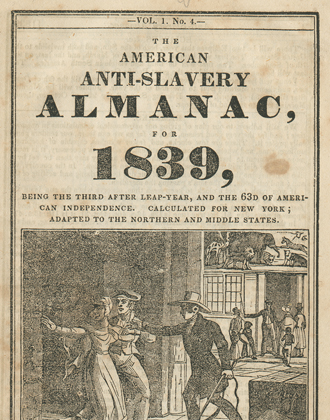

A new set of political activists fled to the emerging city. The abolitionists were a radical minority who had established the American Anti-Slavery Society in Philadelphia in 1833 with headquarters in Manhattan. It was the first movement in American history in which men and women, black and white, came together with mutual purpose – to end slavery immediately and demand political and legal equality for all Americans. In July 1834, anti-abolition riots flared across Manhattan. In response, a number of white abolitionists relocated to Brooklyn, where they joined a thriving anti-slavery movement led by black Brooklynites for over two decades.

The Panic of 1837 led to a decade-long economic depression that ended Brooklyn’s rapid growth. Reduced property prices enticed black New Yorkers to buy land. In doing so they confronted an 1821 amendment to New York State’s constitution which introduced a $250 property requirement for black men to vote while removing all qualifications for white men. Owning property became a political tool that allowed black men to be counted as full citizens with voting rights. The result was the mobilized community of Williamsburg and the vibrant village of Weeksville – where independence, safety, and economic prosperity thrived.

Anti-Colonization Debate

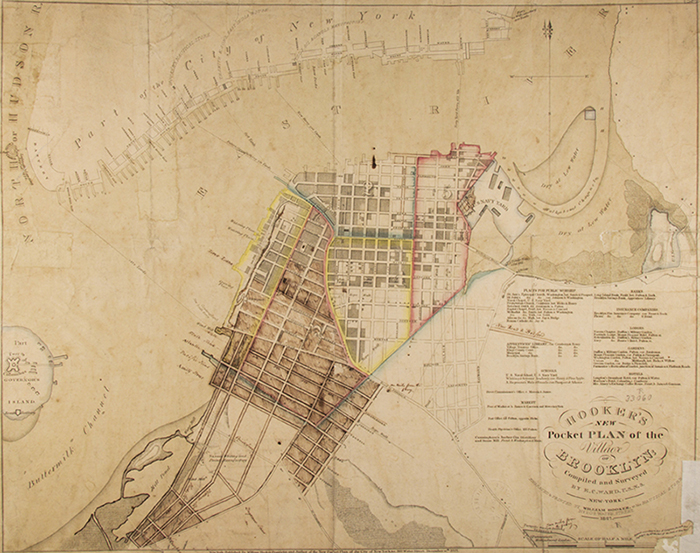

The map shown here represents the village of Brooklyn contained within the town of the same name in 1827 – the same year that slavery ended in New York State. By this time, Brooklyn transformed from Dutch farmland to a bustling town while Kings County’s other five towns remained largely rural.

The town contained ropewalks, taverns, stores, one-story homes, and unpaved streets. Its residents settled around the Fulton ferry landing. These Brooklynites were Irish immigrants, transplants from new England, descendants of the early Dutch and English settlers, and free African Americans. Though racial prejudice and discrimination were widespread, this diverse community of early Brooklynites lived in close quarters, inhabiting the same streets and public spaces. They lived in neighborhoods that are known today as Downtown Brooklyn, Brooklyn Heights, DUMBO and Vinegar Hill.

![[70 Willow Street]. Eugene L. Armbruster. 1922. Eugene L. Armbruster photographs and scrapbooks. V1974.32.99. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/029_full.jpg)

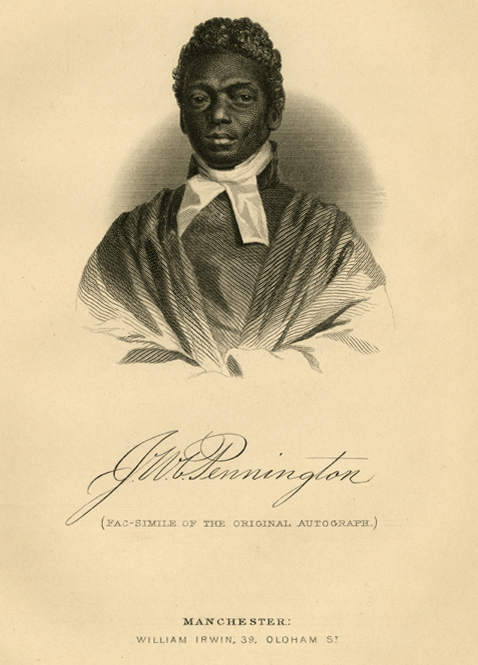

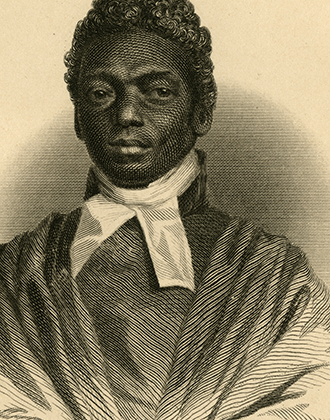

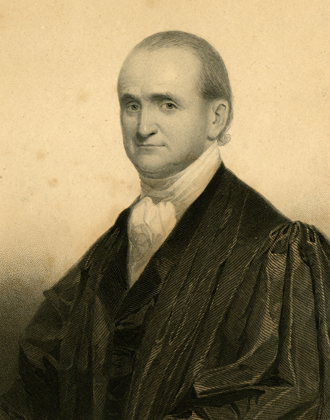

In 1831, Adrian Van Sinderen, president of the Brooklyn Savings Bank, was also president of the Brooklyn Colonization Society, a local branch of the American Colonization Society (ACS). The organization sought to relocate free black communities to Liberia, and Van Sinderen raised a significant amount of money for that purpose. They did not believe American society could or should be culturally diverse. Ironically, James W. C. Pennington, one of the earliest opponents of colonization schemes, worked as Van Sinderen’s coachman. The lives of pro- and anti-slavery activists were intimately intertwined.

![[70 Willow Street]. Eugene L. Armbruster. 1922. Eugene L. Armbruster photographs and scrapbooks. V1974.32.99. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/029_crop.jpg)

![[Certificate of membership]. 1849. Colonization Society of the State of New-York membership certificate to A. Hamilton Bishop. 1985.029. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/030_full_alt.jpg)

Prominent white men founded the American Colonization Society in 1816. The society received support from James Madison, Andrew Jackson, Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and Brooklyn Savings Bank President Adrian Van Sinderen.

Their aim was to send free people of color, born in the United States, to a colony on the west coast of Africa. Many white members argued that racism and slavery were so deeply embedded in American society, relocation was more humane. In fact, the removal of the country’s free black community only strengthened slaveholding interests and avoided the question of equality regardless of race in a democratic society.

![[Certificate of membership]. 1849. Colonization Society of the State of New-York membership certificate to A. Hamilton Bishop. 1985.029. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/030_crop.jpg)

![[Notice of anti-colonization protest in Brooklyn]. The Long Island Star. June 3, 1831. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/031_full.jpg)

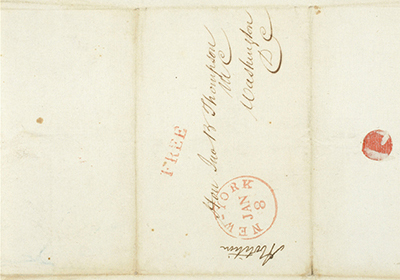

From 1817, free black communities across the North protested the white-led colonization movement. Anti-colonization meetings were held in Philadelphia, Manhattan, Baltimore, and Brooklyn.

On June 3, 1831, a group of Brooklyn’s anti-slavery activists met at the African Hall on Nassau Street to discuss colonization. The meeting was led by Henry C. Thompson (future Weeksville founder), George Hogarth (pastor of the AME Church and educator at the African School), and Pennington (a recent arrival in Brooklyn). Insisting on their right to remain on U.S. soil, they argued:

The colored citizens of this village have, with friendly feelings, taken into consideration the objects of the American Colonization Society, together with all of its auxiliary movements, preparatory for our removal to the coast of Africa; and we view them as wholly gratuitous, not called for by us, and not essential to the real welfare of our race.

Read more...

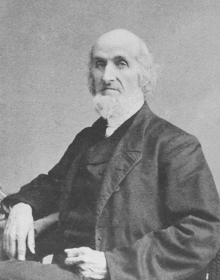

These black led protests inspired a new generation of white activists. Bostonian William Lloyd Garrison, brothers Lewis and Arthur Tappan, and Gerrit Smith were initially sympathetic to colonization. But their views changed after witnessing colleagues speak out against colonization. This radicalization informed, in part, their decision to identify as abolitionists calling for an immediate end to slavery and the denunciation of colonization schemes.

![[Notice of anti-colonization protest in Brooklyn]. The Long Island Star. June 3, 1831. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/031_crop.jpg)

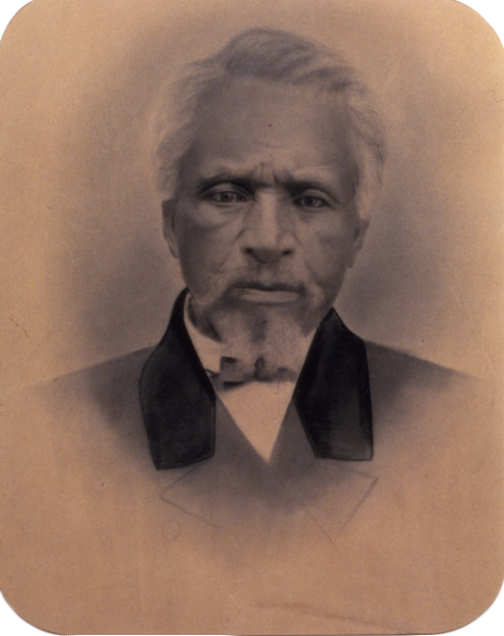

In 1828, a freedom seeker from Maryland arrived in Brooklyn. Born enslaved, James Pembroke changed his name to James William Charles Pennington. As a free man, he worked as a coachman in Brooklyn and enrolled in a Sabbath school in Newtown, Queens. His education emancipated his mind and inspired a lifetime commitment to racial justice.

Read more...

Abolitionism in

Black and White

In the 1830s, the abolitionists, a group of humanitarian reformers, burst onto the political scene in the United States.

On December 4, 1833, sixty-two reformers met in Philadelphia to form the American Anti-Slavery Society, establishing their headquarters in Manhattan. Abolitionism resulted from two political impulses – black activism and white evangelical perfection. As a result, the movement attracted men and women, black and white, from different social classes. It was the first time in U.S. history that activists crossed racial and gender lines to work together with mutual purpose.

Read more...

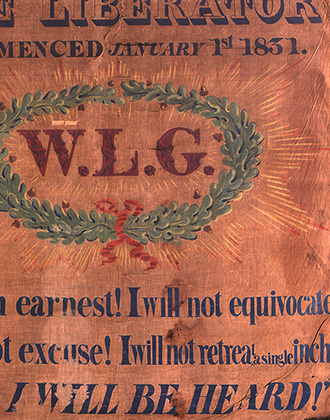

The American Anti-Slavery Society’s brand of abolitionism, or immediatism, became closely associated with Bostonian, William Lloyd Garrison. George Hogarth, pastor of the AME Church and an educator at the first public African school in Brooklyn, was an early supporter of the interracial movement and a Garrisonian. He distributed the Liberator, Garrison’s abolitionist newspaper throughout Brooklyn. It featured letters, poems, news, and notices intended to build a national anti-slavery network.

![[Abolition disclaimer]. The Long Island Star. July 14, 1834. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/037_full.jpg)

Section 2: Lesson 9

Six months after forming the American Anti-Slavery Society, the abolitionist battle against racism and slavery was firmly entrenched in the city of New York.

But the city’s deep economic ties to the South made the situation volatile. In July 1834, the tension erupted. Mobs attacked black and white abolitionist homes and places of worship. They also targeted scores of ordinary black New Yorkers. In the immediate aftermath of these riots, white abolitionists sought to clarify they were radical activists but not anarchists. Two white abolitionists who founded the American Anti-Slavery Society, Arthur Tappan and John Rankin, signed and posted handbills across New York and placed notices in a variety of newspapers including the Long Island Star.

Read more...

Manhattan’s Anti-Abolition Riot became a turning point in abolitionism in Brooklyn. White abolitionists such as Lewis Tappan, Samuel Cox and Joshua Leavitt eventually left Manhattan and moved to Brooklyn, where they built upon a vibrant anti-slavery movement long established by black Brooklynites.

![[Abolition disclaimer]. The Long Island Star. July 14, 1834. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/037_crop.jpg)

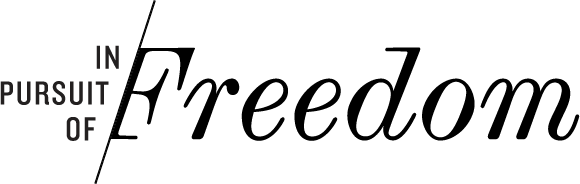

Samuel H. Cox was an abolitionist and pastor in Manhattan.

When Samuel Cornish, the founder of Freedom’s Journal, the first anti-slavery newspaper in the United States, sat in a pew at his church, Cox’s white parishioners reacted in horror.

Read more...

Section 2: Lesson 9

Critics often demonized abolitionists in the press, by arguing that they promoted miscegenation, or interracial relationships, a sexual perversity in their eyes. In doing so they belittled the abolition movement which represented the first time that Americans crossed race and gender lines to work with mutual political purpose.

Prints such as E. W. Clay’s “Fruits of Amalgamation” reflected the contemporary prevalent racism and hostility towards the abolitionists’ interracial cooperation.

Print Propaganda

Section 2: Lesson 9

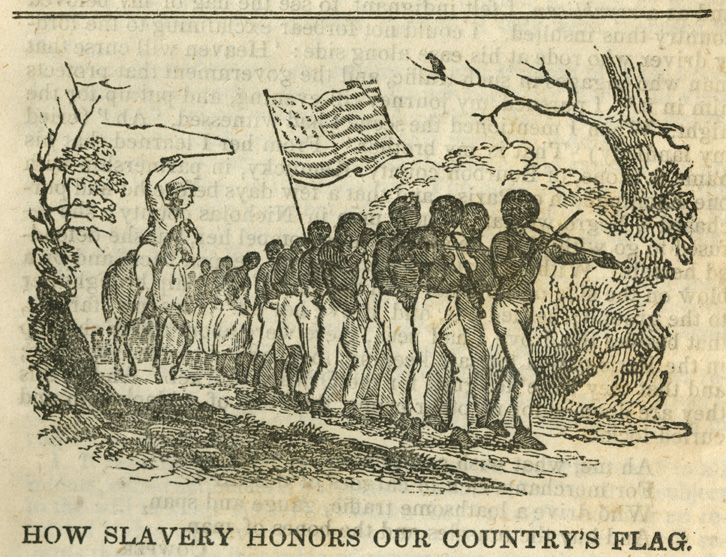

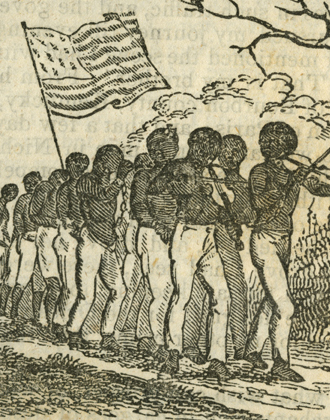

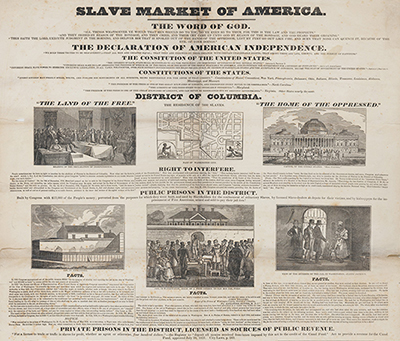

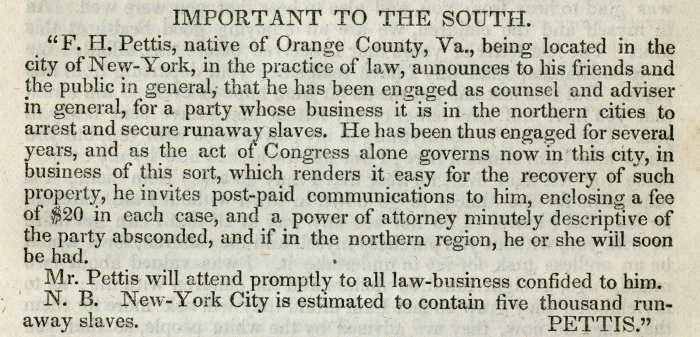

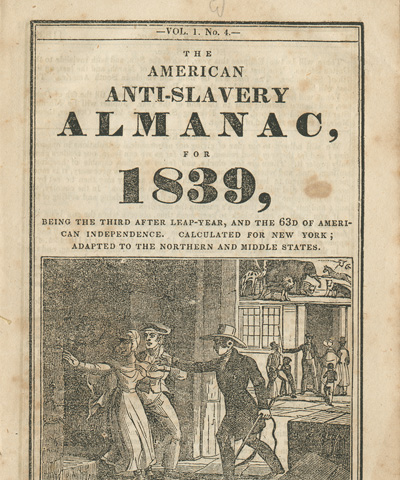

In May 1835, less than a year after the anti-abolition riots, the American Anti-Slavery Society reported that it had published over 1 million pieces of printed material. The sophisticated print propaganda campaign furthered their anti-slavery agenda. It took advantage of newer print technologies that allowed for materials to be cheaply mass-produced. Anti-slavery propaganda included illustrated periodicals, newspapers, pamphlets, and broadsides.

The abolitionists bombarded the federal postal service with anti-slavery materials. Lewis Tappan led the postal campaign despite threats of violence. Thousands of anti-slavery publications were sent to post offices in the North and South intended to persuade readers that slavery was a sin through moral suasion. But the avalanche of materials incited violence in Charleston, South Carolina. On July 29, 1835, a mob descended on the post office, and burned both the bags and mock effigies of Lewis Tappan and William Lloyd Garrison.

Section 2: Lesson 9

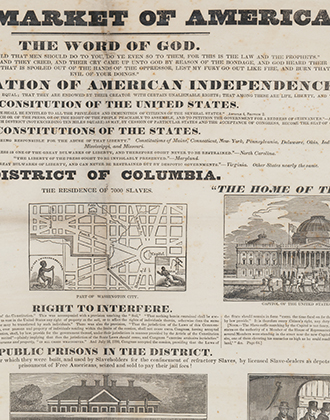

Anti-slavery print materials conveyed slavery’s horrors including sexual abuse and physical suffering. “Slave Market of America” emphasized American hypocrisy by showing slavery in the capital city of a nation founded on the premise of liberty.

The visual language of anti-slavery prints was intended to persuade the most cynical of audiences. Consequently, it erased black agency, casting African Americans as victims. These images removed achievements of black people – free and enslaved – from the visual record, leaving behind a complicated historical legacy.

![[Cover of Annual Report of the Brooklyn Anti-Slavery Society] printed by W.S. Dorr, 1840. Negative #85469d. Collection of The New-York Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/049a_full_alt.jpg)

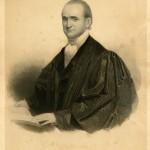

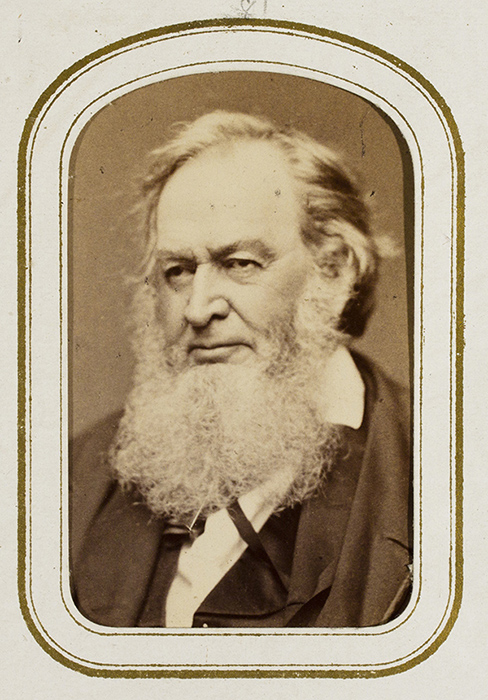

In 1839, white abolitionists founded the Brooklyn Anti-Slavery Society, an auxiliary of the American Anti-Slavery Society. The organization promised to organize prayer meetings and public lectures so that Brooklynites could “sympathize with human woe.” Abolitionists were able to spread their message quickly through such local groups, including female auxiliaries, established throughout the North.

Read more...

The Society’s founders were John Rankin, Edward Corning, and William E. Whiting, all white men from the merchant class, and ardent abolitionists. They were also residents of Brooklyn Heights, a neighborhood particularly welcoming to wealthy people who worked in the financial epicenter of lower Manhattan.

![[Cover of Annual Report of the Brooklyn Anti-Slavery Society] printed by W.S. Dorr, 1840. Negative #85469d. Collection of The New-York Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/049a_crop.jpg)

Practical Abolitionism

New York’s cultural, economic and political ties to the South ran deep, and it became a fertile hunting ground for slavecatchers in the post emancipation decades. The city’s judges often favored the slavecatcher. The problem was so percasive that abolitionist David Ruggles promised to publish a “Slaveholders Directory with names; residences of all members of the bar, police officers, city marshalls, constables, and other persons who lend themselves in the nefarious business of kindnapping and the names of slaveholders residing in the city of Brooklyn.”

The kidnapping of free black people was prevalent in New York and Brooklyn. Anti-slavery materials, intended to convince readers of slavery’s moral bankruptcy, proved insufficient. In response, abolitionists formed the New York Vigilance.

Twenty-six year old David Ruggles, born free in Connecticut, emerged as its most visible activist. He combined the print propaganda tactics of the American Anti-Slavery Society with a new form of activism. Historian Graham Hodges labeled it a “practical abolitionism.” Ruggles physically intervened in many cases and this came to typify the style of his anti-slavery activity.

David Ruggles, born free in Connecticut, led the New York Vigilance Committee, pioneering a practical abolitionism. He often risked his life to physically intervene in the abduction of free black people in Brooklyn and New York.

Kidnapping in Brooklyn

Margaret Baker and her children were living at the Brooklyn Almshouse in Flatbush, when they were kidnapped the family and sold into slavery. Ruggles approached Land Van Nostrandt, the overseer of the Almshouse, at his home and demanded the family’s return. The historical record does not reveal whether or now he was successful.

Read more...

Ruggles charged the Dodges with couple with the enslaved people captive for years. He burst into their home and an argument ensued. Ruggles eventually succeeded in legally emancipating Jesse, Jim and Charity. But white abolitionists criticized his aggressive style of activism. Despite their mutual purpose, black and white abolitionists did not always agree. In 1839, Ruggles was forced to resign from his position with the New York Vigilance Committee.

Amistad

In 1839, the Amistad, a Spanish schooner from Cuba containing 59 enslaved Africans was found shipwrecked off the coast of Long Island. Joseph Cinque, a Sierra Leonean, and others had overthrown the crew and demanded to be taken back to Africa. Instead the Spanish crew commandeered the schooner towards the American coast and asked for government protection. The African survivors were taken to New London, CT, imprisoned and charged with piracy and murder.

Brooklyn abolitionists Simeon Jocelyn, a Williamsburg resident, and Lewis Tappan, a Brooklyn Heights resident, worked closely with the African prisoners, and after a high-profile court case, they were freed.

Later, Jocelyn and others, formed the American Missionary Association, an organization dedicated to abolitionism through evangelicalism. During Reconstruction, they concentrated on educational activities.

Land, Voting,

Citizenship: Weeksville

Section 3: Lesson 11

Established by 1838, Weeksville was one of New York’s earliest and most successful black communities intended as a political base.

Sylvanus Smith was a free black man living in the village of Brooklyn. He was one of the earliest land investors in Weeksville, a free black community that thrived during the antebellum decades.

Read more...

The town of Brooklyn was transformed by land speculation during the early nineteenth century. In 1804, Hezekiah Beers Pierrepont, a pioneering developer purchased a sixty-acre farm in Brooklyn Heights. When his friend, Robert Fulton, developed the steam ferry that reduced commuting times between Brooklyn and Manhattan, the first U.S. suburb was born. By 1817, Pierrepont owned most of Brooklyn Heights and began to parcel it off to individual land investors. In 1834, Brooklyn had outgrown its suburban status and was an independent city.

But the Panic of 1837 brought Brooklyn’s rapid urbanization to an end. Property prices plunged and stayed low as a ten year economic depression followed.

Founding of Weeksville

Just one year following the Panic, free black Brooklynites including Smith intentionally founded the village of Weeksville. In 1821, the New York State Constitution eliminated all property qualification for white men and introduced a $250 property requirement for black men. Weeksville was established, in part, as an answer to this discrimination. Brooklyn’s free black community created a landowning community that would support them as full citizens with voting rights.

![Chancery Sale of Real Estate Belonging to the Heirs of Samuel Garrittsen, decd., situated in the 9th Ward of the city of Brooklyn. George Hayward. 1839. B P-[1839].Fl. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/061_full.jpg)

Section 3: Lesson 11

African Americans began to acquire land in the city’s ninth ward, the most distant and secluded of Brooklyn’s wards from the bustling downtown area as early as 1832.

Three years later, Henry C. Thompson purchased 32 lots in the area indirectly from John Lefferts’ estate. In 1838, James Weeks, an African American longshoreman, purchased two lots. He was the only original land investor to reside in the area and for whom Weeksville was named.

![Chancery Sale of Real Estate Belonging to the Heirs of Samuel Garrittsen, decd., situated in the 9th Ward of the city of Brooklyn. George Hayward. 1839. B P-[1839].Fl. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/061_crop.jpg)

![[Hunterfly Road Houses]. Eugene L. Armbruster. 1922. Eugene L. Armbruster photograph and scrapbook collection. V1987.11.2. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/062_full.jpg)

Section 3: Lesson 11

The Hunterfly Road Houses are the last remnant structures of the once thriving community of Weeksville. It was the second largest free black community in antebellum America.

Historian Judith Wellman’s research shows that it boasted high levels of homeownership and it was the only free black community with an urban rather than rural economic base. By 1855, it had 521 residents.

![[Hunterfly Road Houses]. Eugene L. Armbruster. 1922. Eugene L. Armbruster photograph and scrapbook collection. V1987.11.2. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/062_crop.jpg)

Junius Morel was a long serving educator at Colored School #2, or the African School in Weeksville. He was also a prominent activist and a national correspondent for a variety of anti-slavery newspapers.

It is no coincidence that the majority of educators in Brooklyn’s African Schools were anti-slavery activists. Education was a powerful weapon to fight racism and inequality. Henry C. Thompson, Sylavnus Smith, and George Hogarth were all instrumental in establishing the African School in what is now Downtown Brooklyn and used the resources at the AME Church to do so. Willis and William Hodges and their neighbors founded the African School in Williamsburg.

Read more...

Land, Voting,

Citizenship: Williamsburg

“[It is] my opinion that the people of color have to leave the crowded cities and town of New York, Brooklyn, Syracuse, Albany, Troy, Utica and the rest and move into country and small growing villages like Williamsburg, and grow up with a small town. I believe in that way they would overcome much of the prejudice against them, for, as a rule, there is a fraternal feeling between the people of small towns or places (even in the South) that is unknown in the large cities.”

Willis Hodges, A Free Man of Color.

In 1839, at the height of Williamsburg’s land speculation, William Hodges, a free man from Norfolk, VA, bought his first plot of land there. He erected his home at the corner of 4th Street (modern day Bedford) and South 8th Street, a highly desirable location, and a short walk to the Peck Slip Ferry with views of the city. His brother Willis moved nearby to South 7th Street where he lived with his wife Sarah Ann Corprew, whose parents lived in Weeksville.

Read more...

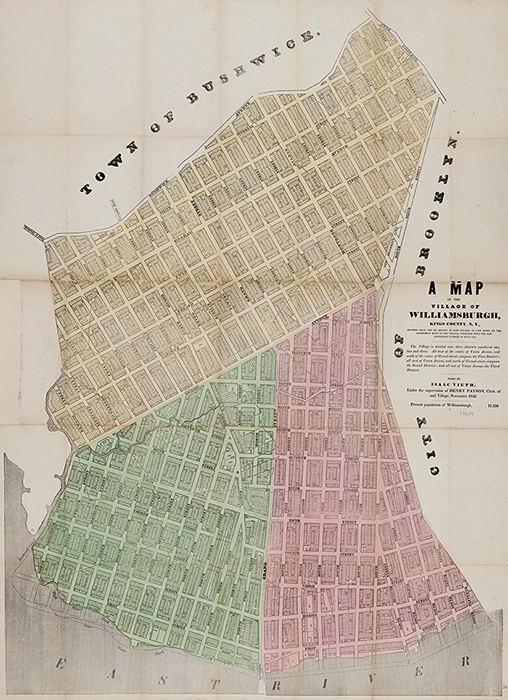

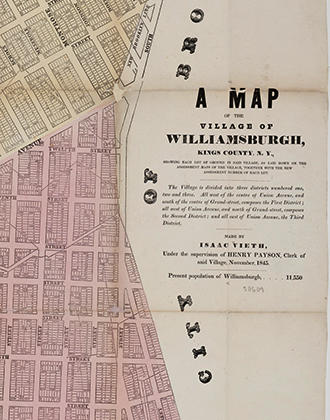

Until 1855, Williamsburg was separate from the city of Brooklyn. It was part of the town of Bushwick, one of Kings County’s original six towns and remained distinctly rural until its incorporation as a village in 1827. During Williamsburg’s early growth, the village council opened and improved streets, dug wells, and established a district school.

In 1829, Williamsburg had a post office, 148 homes, 10 stores and taverns, 5 ropewalks, 1 distillery, 1 slaughterhouse, 2 butchers, a Dutch Reformed Church, and a Methodist Episcopal Church.

Just six years later, its population had tripled to 3,000. There were 72 village streets, approximately 300 houses, a newspaper called the Williamsburg Gazette. In 1836, two ferries connected the growing town of Williamsburg to New York. In 1852, it received a city charter and was complete separate from the town of Bushwick in which it had originally started.

![48 valuable lots in the village of Williamsburgh, Kings County. 1845. B P-[1845].Fl. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/065_full.jpg)

Williamsburg’s growth was made possible by developers who recognized its commercial advantages. The land stood 45 feet above water which prevented it from flooding, it looked out at a waterfront that stretched 1.5 miles along the East River, and it was in close proximity to the financial hub of Manhattan. The influx of merchants, industrialists, and laborers, mostly from Germany, transformed Williamsburg from a village (1827) to a town (1840) to a city (1852) that was eventually annexed to Brooklyn in 1855. Home to the second largest black community in Kings County, Williamsburg was a bastion of anti-slavery activity.

![48 valuable lots in the village of Williamsburgh, Kings County. 1845. B P-[1845].Fl. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/065_crop.jpg)

![[Public School 191]. Eugene L. Armbruster. 1929. Eugene L. Armbruster photograph and scrapbook collection. V1991.106.125. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/070_full.jpg)

Section 3: Lesson 12

In 1841, Williamsburg activists opened an African School after the village school refused admission to approximately 40 students of color aged 5 to 16.

Willis Hodges, William Hodges, Samuel Ricks, Lewis H. Nelson, Thomas Wilson, and Henry Davis raised funds and formed the school committee. William Hodges was elected to act as both teacher and principal. When the Brooklyn Board of Education took over the management of all public schools, the African School in Williamsburg was renamed Colored School #3. Abolitionist Maria Stewart and Weeksville founder Sylavnus Smith’s daughter Sarah J. Tompkins Garnet were among its many educators.

![[Public School 191]. Eugene L. Armbruster. 1929. Eugene L. Armbruster photograph and scrapbook collection. V1991.106.125. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/070_crop.jpg)

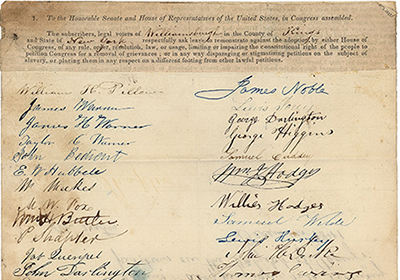

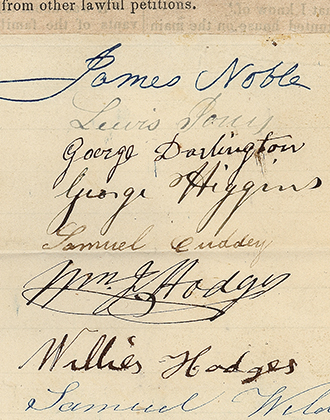

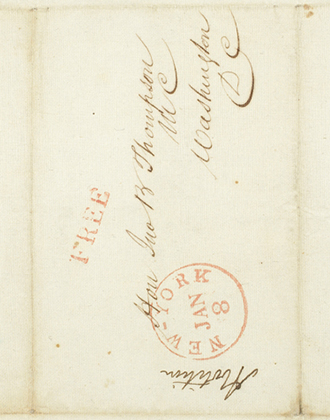

In 1841, Williamsburg’s black and white voters used new and old tactics to fight slavery. They showed support for the newly formed Liberty Party which reflected their anti-slavery stance. But they also used the decade old strategy used by abolitionists of petitioning Congress.

Beginning in the early 1830s, abolitionists advocated for the end of slavery by petitioning state legislatures and the House of Representatives. It is estimated that the American Anti-Slavery Society sent more than 600,000 anti-slavery petitions containing over 2 million signatures in total. Congress responded to the onslaught of these petitions by passing a series of resolutions between 1836 and 1844 that tabled them, known as the gag rule.

This petition asks Congress to remove the gag rule placed on anti-slavery petitions. Signatures came from James Warner, his son James H. Warner, Taylor C. Warner, Samuel Shapter, William Hodges, and Willis Hodges. These men knew each other through their Liberty Party activities.

In 1840, abolitionists divided into two ideological camps: the Garrisonians and Tappanites. The split occurred because Lewis Tappan felt that William Lloyd Garrison was becoming too radical. In particular, he insisted that women be allowed to serve alongside men on the executive committee of the American Anti-Slavery Society (until then women had worked in separate anti-slavery societies).

The split continued to give rise to new strands of anti-slavery activism. In particular, black activists recognized the need for a two-pronged approach – a demand for the end to slavery and a redress of basic civil rights for all people of color.

Read more...

On December 29, 1841, Kings County activists met in Williamsburg to show their support for the Liberty Party. The meeting was led by James Warner, a hatmaker, who had first met William Hodges at an American Anti-Slavery Society gathering. For William Hodges, and countless men like him, the support for party politics was a reaffirmation of the full privileges of citizenship with voting rights. The Liberty Party dissolved by 1848 having failed to get a foothold in national politics.

Gerrit Smith was a wealthy white landowner and abolitionist. He established a utopian community called Timbuctoo on 120,000 acres of his own land in the Adirondacks. Between 1846 and 1853, Smith donated 40-60 acre lots to 3,000 African American men, creating a community of black voters in New York State. Timbuctoo was a response to New York’s failure to amend the voting requirements for black men in 1846 and the continued protest for black citizenship.

Gerrit Smith’s Timbuctoo valued independence, self-sufficiency, and community. Residents were expected to live off the land while being able to escape some of the racism they encountered on a daily basis. Many Kings County residents participated in the democratic experiment including Willis Hodges. But life in Timbuctoo was difficult. They were unprepared as farmers, lacked basic supplies, and faced a dearth of fertile soil. By the mid-1850s, Timbuctoo was no longer operational.

Pingback: » Remembering Joan Maynard – Weeksville Heritage Center Visionary