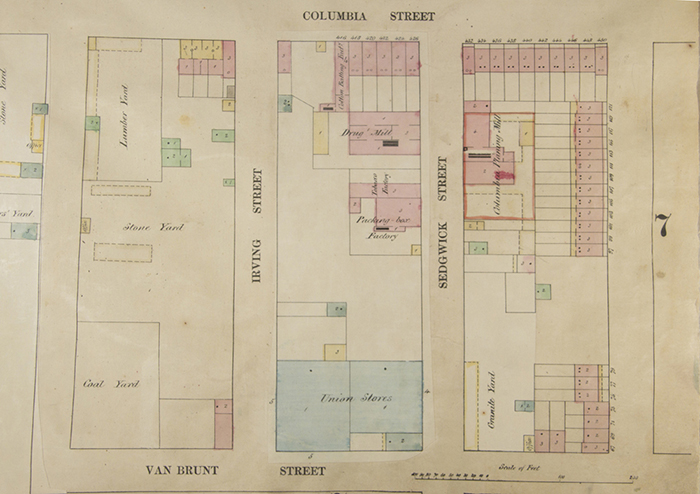

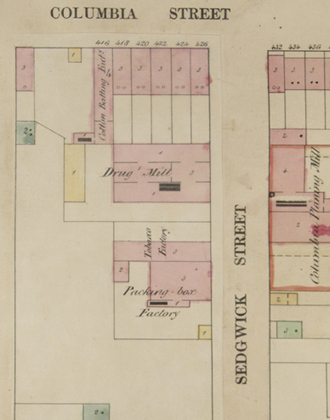

The Irish and Black communities were among the most marginalized in American society. They often competed for the same low paying, low-skilled jobs. During the Civil War, the Irish came to fear that fugitives and newly emancipated men and women would arrive in Brooklyn and take the few jobs available, exacerbating hostilities. In the summer of 1862 Irish mobs attacked men and women at the Tobacco Factory on Sedgwick Street in Brooklyn. The Tobacco Factory Riots foreboded Manhattan’s Draft Riots that erupted a year later. Few could have foreseen its immense and devastating consequences.

At the end of the War, emancipation came without equality. During Reconstruction, African Americans in Brooklyn and beyond faced intense hostility and difficulties with education, employment, housing, and voting. Nevertheless, Brooklyn’s abolitionists and anti-slavery activists continued the struggle for equality, using their proven organizing skills to help rebuild the nation.

Women & Abolitionism

![[School Yard, Colored Orphan Asylum]. Association for the Benefit of Colored Orphans Records, The New-York Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/150_full.jpg)

The abolition movement, from its emergence in the 1830s, allowed women to seize expanded opportunities outside of the traditional roles of mother, daughter, and wife.

Female abolitionists in Brooklyn and beyond ran mutual-aid, anti-slavery, and literary societies to improve their local communities.

In particular, black women across Brooklyn and New York worked to fund Manhattan’s Colored Orphan Asylum. Founded in 1835 by Anna Shotwell and Mary Murray, two white Quaker women, the Colored Orphan Asylum provided an essential service in antebellum New York. For African Americans living in poverty, the Asylum offered a temporary refuge. Parents could send the children to the asylum to receive better care – often an agonizing decision –while they improved their own economic circumstances at home.

On February 22, 1860, organizers held a four-day fair at Montague Hall, next to Brooklyn’s City Hall. The fundraiser “brought together all the elite and fashion of this portion of the Anglo-African world, and much of the Anglo-American in the bargain.”

Read more...

The fair raised $1,100 (or about $30,000 today) for the Colored Orphan Asylum.

![[School Yard, Colored Orphan Asylum]. Association for the Benefit of Colored Orphans Records, The New-York Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/150_crop.jpg)

![[Borough Hall with Montague Street on right]. 1880. Eugene L. Armbruster photographs and scrapbooks. V1974.1.1299. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/151_full.jpg)

In 1834, the Remsen and Pierrepont families donated land for the construction of a grand City Hall to reflect Brooklyn’s new city status. After fourteen years of construction, City Hall stood tall on the edge of Brooklyn Heights.

In the early 1860s, the streets surrounding City Hall developed quickly, and organizations such as the Brooklyn Academy of Music (1861), Long Island Historical Society (1863), and the Mercantile Library Association (1868) formed a cultural hub there. Montague Hall, where Brooklyn’s female anti-slavery activists held a four-day fair to raise funds for Manhattan’s Colored Orphan Asylum, often served as a venue for the city’s many reform societies.

![[Borough Hall with Montague Street on right]. 1880. Eugene L. Armbruster photographs and scrapbooks. V1974.1.1299. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/151_crop.jpg)

Black Soldiers

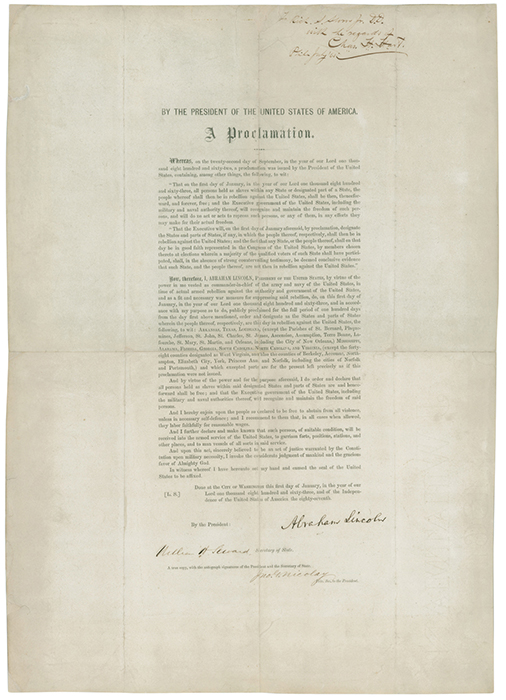

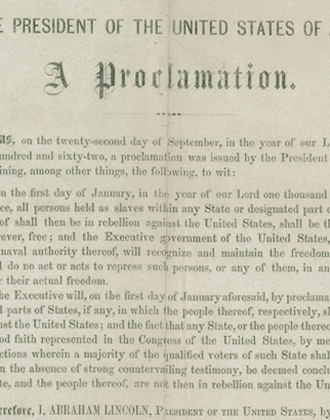

On January 1, 1863, Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation took effect.

All persons held as slaves within any state […] in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.

Read more...

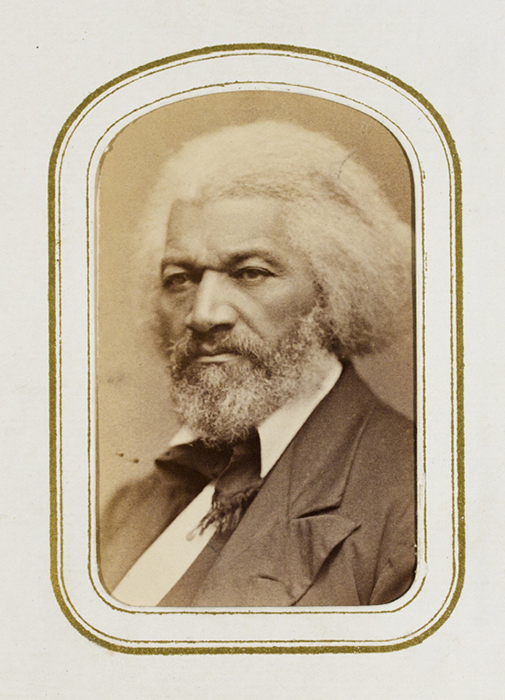

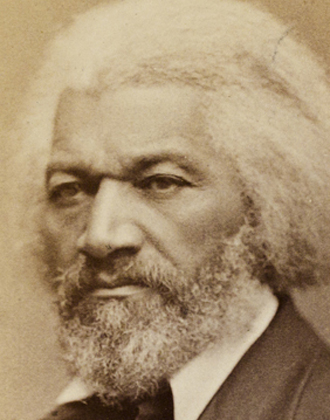

On May 15, 1863, Frederick Douglass appeared at the Brooklyn Academy of Music on Montague Street, where he spoke to a packed house. In a fiery speech, Douglass argued that black men had been “regarded only as the means of putting money in the white man’s pocket, like a bale of cotton, but hereafter he must be regarded as a man.”

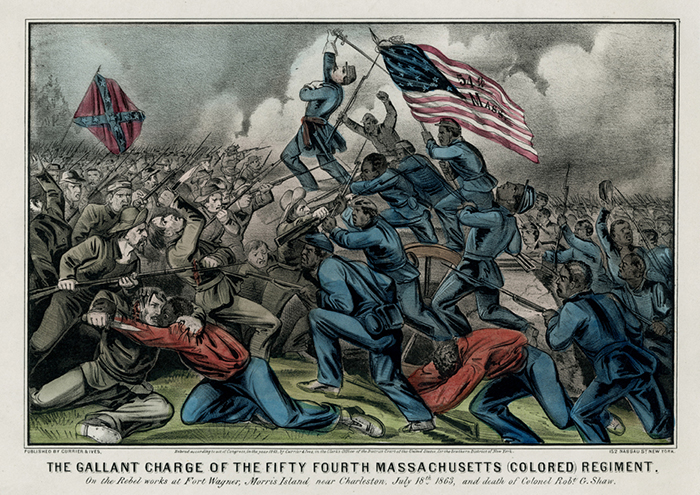

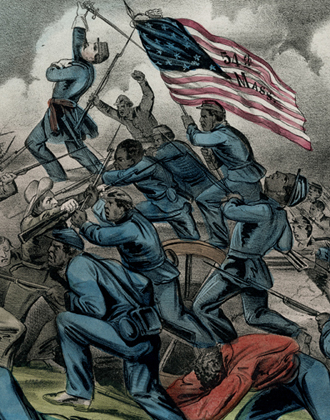

Douglass and other abolitionists, including James W.C. Pennington, believed that African Americans would be central to a Union Army victory despite the fact that they were initially banned from serving. He concluded his speech by praising the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, the first black regiment raised in the North, and hoped to see them march down Manhattan’s Broadway to the music of “Old John Brown.”

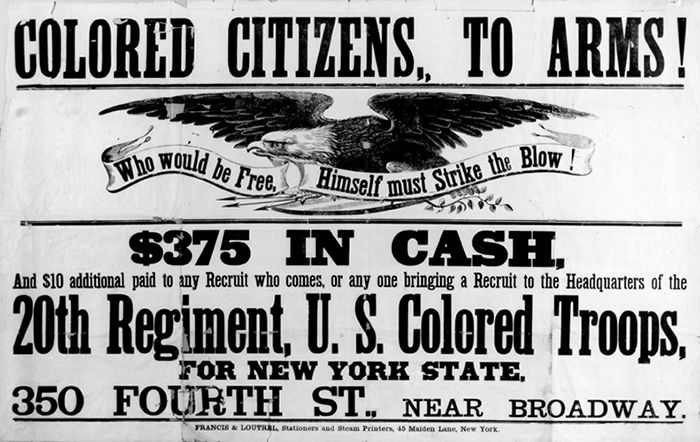

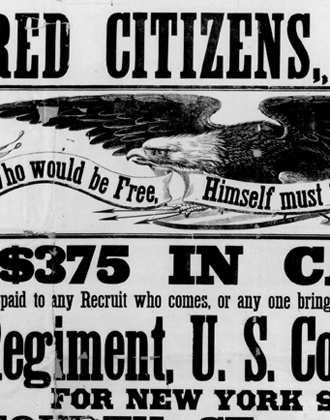

After the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect, the Union Army began allowing African American men to enlist for the first time. Despite receiving lower wages, poor supplies, and lesser chances for promotion than their white colleagues, these men demonstrated tremendous bravery to end slavery and be recognized as equal citizens of the United States.

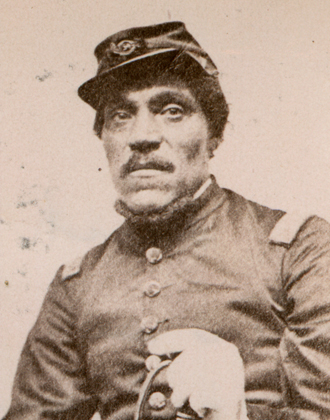

Peter Vogelsang was among the thousands of ordinary black men who demonstrated their courage and patriotism while being subject to difficult conditions including ongoing discrimination, segregated ranks, lesser wages, and lack of military promotion. They protested for improved conditions while fighting for the future of the nation. In turn, African Americans pushed for a culturally diverse society and the right to be counted as citizens.

Read more...

On July 18 1863, two days after the Draft Riots, the Massachusetts 54th Infantry the first black regiment raised in the North, led an attack on Fort Wagner. Their hope was to break the network of Confederate defenses protecting Charleston, South Carolina. The Confederates, protected by a strong fort, completely overpowered the Union attackers, leaving half of them wounded, captured or killed. Their experience was depicted in the movie Glory.

Tobacco Factory Riot & Draft Riots

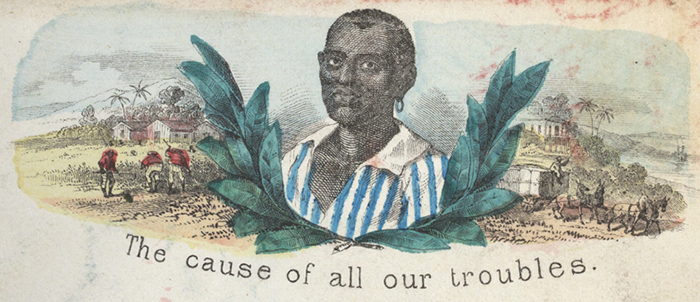

Ironically, many Americans blamed black people for the Civil War, especially following the Emancipation Proclamation, when ending slavery became an explicit goal. This ugly resentment towards African Americans erupted during Brooklyn’s Tobacco Factory Riots (1862) and Manhattan’s Draft Riots (1863).

Brooklyn’s Tobacco Factory Riots (1862) were an important and often overlooked precursor to the Manhattan’s Draft Riots (1863).

In August 1862, African American workers, mostly women and children, were assaulted by Irish mobs at the Tobacco Factory on Sedgwick Street in Brooklyn. Even the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, often responsible for some of the most derogatory passages about black Brooklynites during the 19th century, wrote:

We regret most profoundly that, a city, so justly celebrated for its law and order as Brooklyn, should have been so disgraced.

Fear that fugitives and newly emancipated people would move to Brooklyn and take scarce jobs exacerbated hostilities between Irish and African American workers. The Irish, impoverished and marginalized themselves, had emigrated to America to escape the horrors of Ireland’s devastating Potato Famine between 1845 and 1852. But they were greeted with discrimination and limited economic opportunities. Irish immigrants and African Americans competed for the same occupations as laborers, waiters, servants and washerwomen.

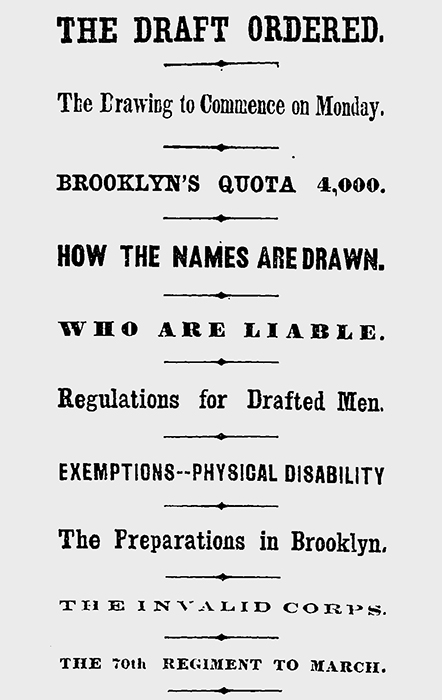

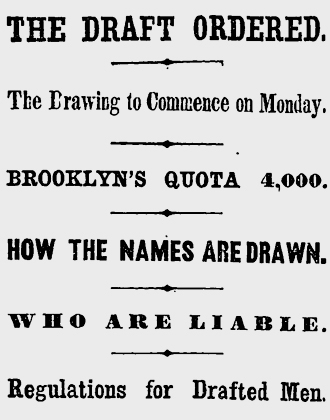

In March 1863, Congress passed the National Conscription Act which allowed men to pay $300 to avoid the draft, a sum of money that only the wealthy could afford (it represented a year’s wages for a working class man). Many Irish already resented the draft because they felt no political connection to a war about slavery. They turned their wrath towards their black neighbors.

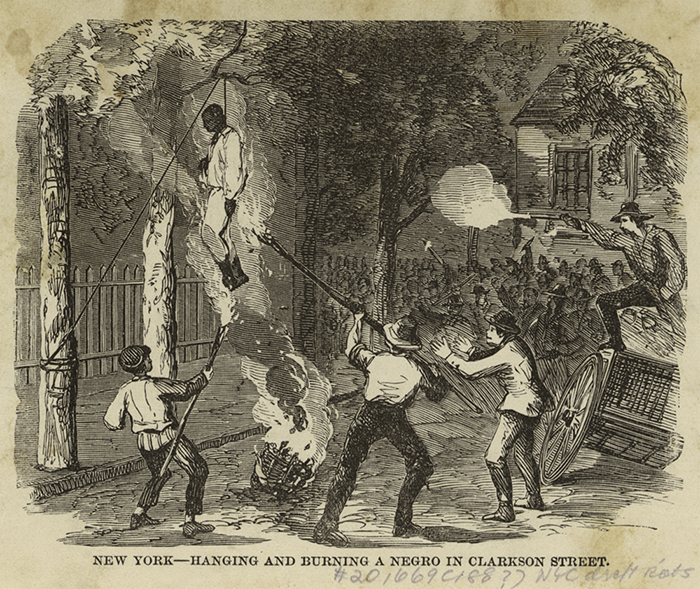

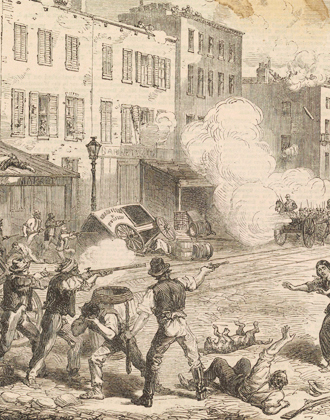

From Monday, July 13 to Thursday, July 16, 1863, mobs of white people, mostly working class Irishmen, tore through Manhattan’s streets. What began as a mass protest against the draft turned into a full-blown riot. Mobs attacked public buildings, businesses, the mayor’s residence, police station, the Armory and the Colored Orphan Asylum. Some of the worst atrocities were committed against black New Yorkers.

New York’s Draft Riots remain the largest and bloodiest urban insurrection in U.S. history.

Black New Yorkers suffered the worst atrocities in the Draft Riots. A twenty-year-old disabled man named Abraham Franklin called at his mother’s house to check that she was safe. Before he was able to leave her house, a mob burst in and beat Franklin before lynching him and mutilating his body.

15-year-old Maritcha Lyons was among the many terrified African Americans who fled their homes in Manhattan during the city’s Draft Riots. The Lyons family were prominent anti-slavery activists. Maritcha, her sister, her mother Mary, and father Albro all ran to Brooklyn for safety and refuge. They never returned to Manhattan. As an adult, Maritcha dedicated her life to Brooklyn’s public schools.

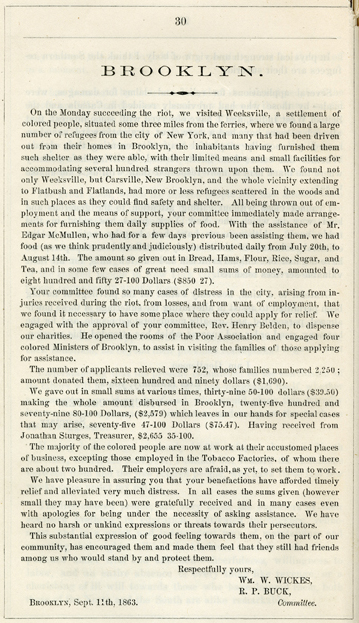

Brooklyn was a place of refuge for black New Yorkers escaping the terror of Manhattan’s Draft Riots. Many escaped to Weeksville. Others went to the Turn Verein Hall in Williamsburg where German Brooklynites ensured their safety.

As this document shows, Brooklyn became a safe heaven for countless New Yorkers during the Draft Riots in July 1863. The riots left nearly 3000 black New Yorkers homeless.

Reconstruction

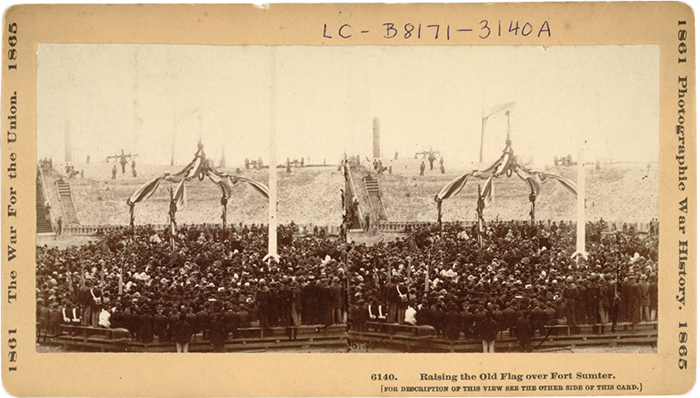

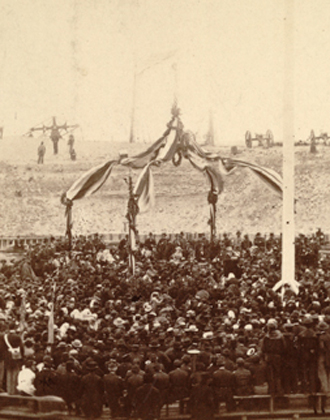

In April, 1865 the Civil War ended. Henry Ward Beecher, perhaps Brooklyn’s most recognizable abolitionist, attended the flag raising ceremony at Fort Sumter. Three decades after abolitionists had begun the campaign to end slavery in the United States, emancipation finally arrived for all. But true equality still eluded many Americans.

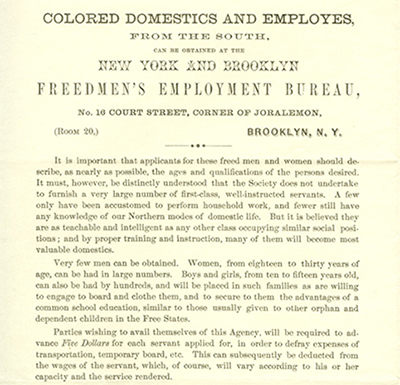

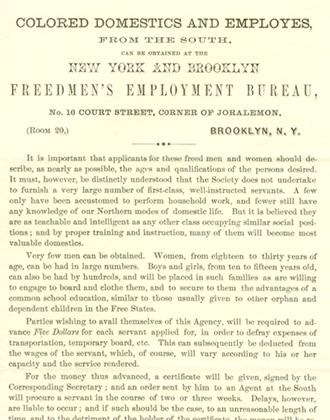

On March 3, 1865, Congress created the Freedmen’s Bureau. It was intended to provide employment opportunities for newly emancipated people and white veterans. The New York and Brooklyn Freedmen’s Bureau was located on the corner of Court and Joralemon. Brooklynites could hire children aged 10 to 15 years old and women aged 18 to 35. Most would have worked as domestic servants.

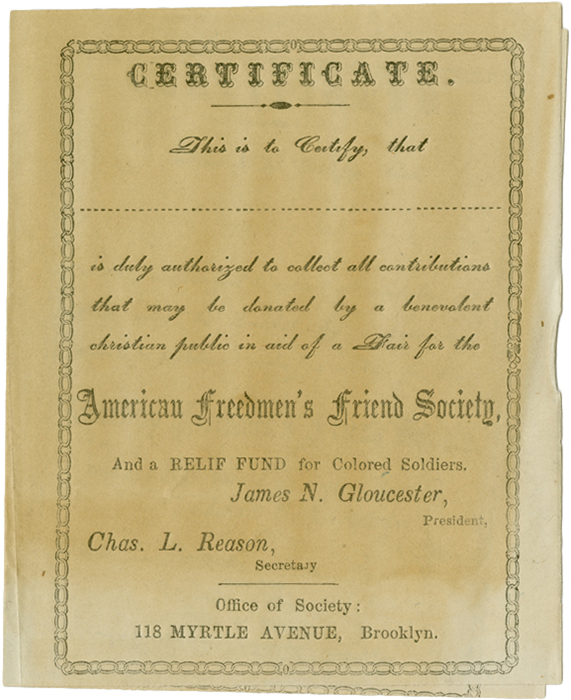

The Civil War brought freedom without equality. Elizabeth and James Gloucester established the local American Freedmen’s Friend Society in Brooklyn. Unlike the Freedmen’s Bureau, this was a grassroots organization run by local black communities. The organization accepted clothes, books, money and general goods to support newly emancipated people and veterans.

Many Brooklynites used their vast experience as anti-slavery activists to rebuild the nation. They focused on areas such as employment, housing and education.

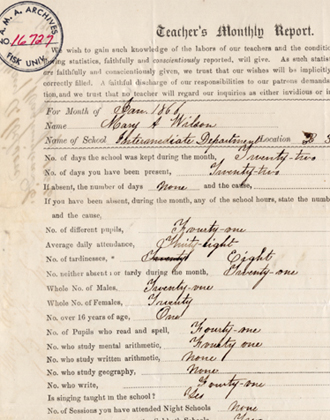

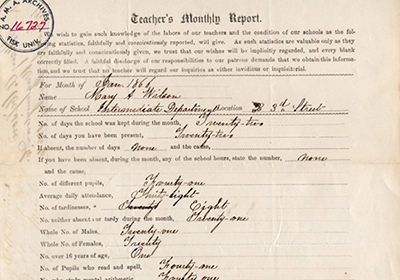

During Reconstruction, William J. Wilson the longest serving educator at Colored School #1 in Brooklyn, his wife Mary, and their daughter Annie moved to the South to teach newly freed African Americans. Mary and Annie Wilson taught at the Frederick Douglass Freedmen School in Washington, D.C.

Many African Americans moved to the South after the Civil War to take up leadership positions. William Hodges left Williamsburg and returned to his birthplace Norfolk, Virginia, where he opened a school for African Americans. William and his brother Willis toured throughout the region and lectured audiences on voting rights.

Others, like the Gloucesters, stayed in Brooklyn continuing to agitate for social justice. When Elizabeth died in 1883 she was one of the richest women in the United States.