The city itself continued to rapidly expand, this time along its extensive waterfront. Sugar, tobacco and cotton – all valuable commodities produced by unfree labor – lined the city’s warehouses. By 1855, Brooklyn was central to the business of slavery.

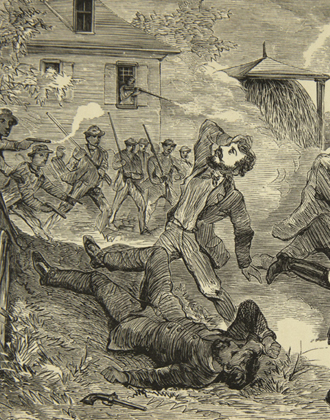

As sectional tension intensified, Brooklynites were divided on the issue of slavery. Residents were tested as a series of crises on slavery unfolded: the Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854), the Dred Scott Decision (1857), and the Harpers Ferry Raid (1859). By the end of the decade, violent conflict seemed inevitable.

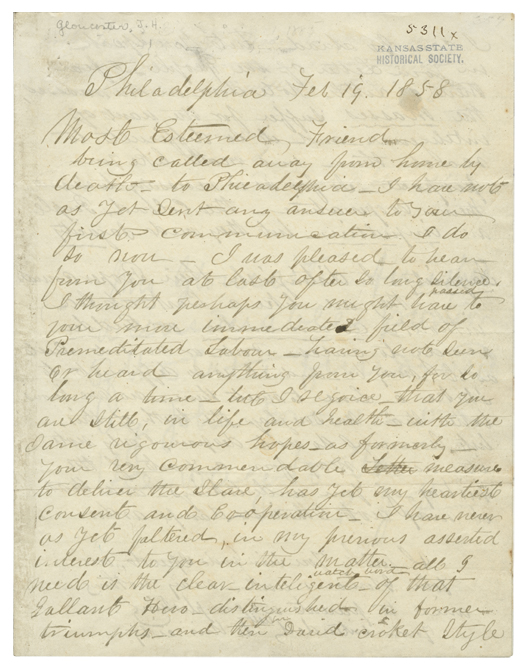

Fugitive Slave Law

By the 1840s, as Brooklyn expanded, many white Brooklynites pushed for greater police protection.

Yet, for the most part, the creation of a city police force represented a threat to black Brooklynites who were unprotected by local, state and federal laws. In 1842, Edward Saxton was accused of being a fugitive from Mobile, AL. His captor, J.C. Gantz presented a Brooklyn Court with an affidavit claiming that Saxton had forged his freedom papers. Officer Barkaloo and Gantz then arrested Saxton at Mansion House, a hotel located on Hicks between Pierrepont and Clark. Saxton was taken from New York to a Baltimore jail.

Read more...

Section 15: Lesson 15

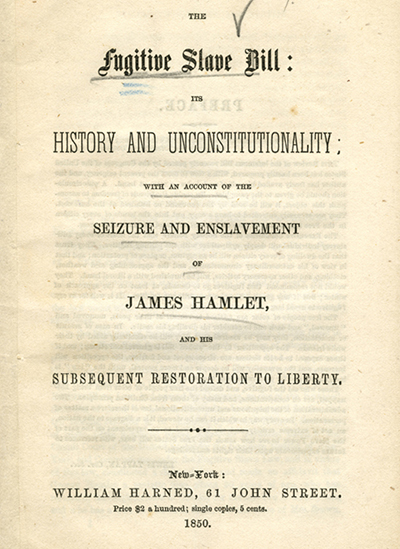

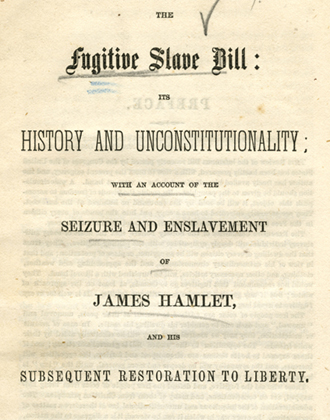

On September 26, 1850, Williamsburg resident James Hamlet, was arrested near his workplace in Manhattan. The arrest was based entirely on his alleged enslaver’s accusation that Hamlet was a fugitive. Under the Fugitive Slave Law, Hamlet was not permitted to testify on his own behalf and he was not entitled to a trial by jury. He was imprisoned and taken to Baltimore.

Read more...

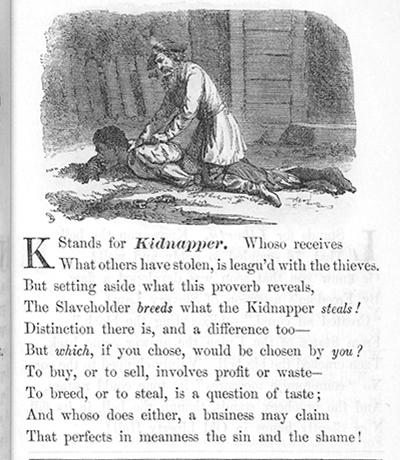

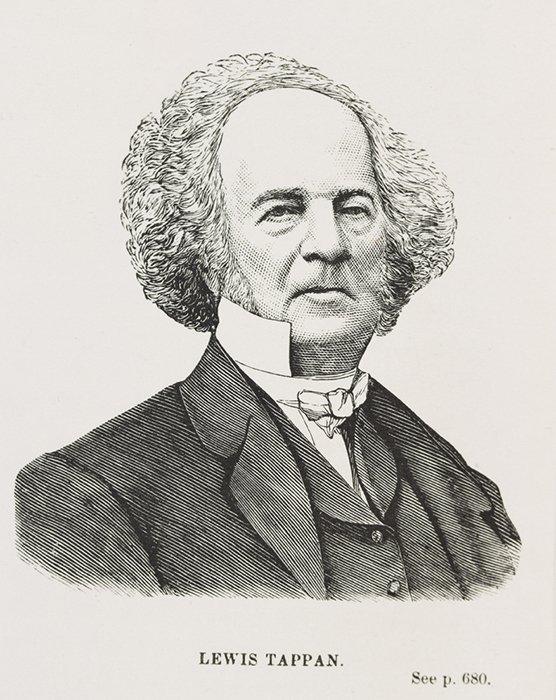

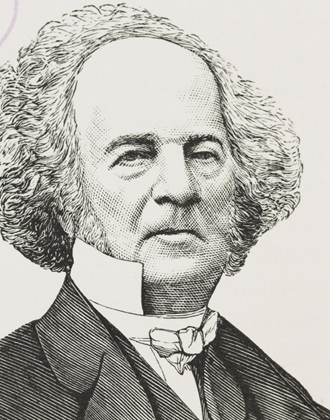

The pamphlet also raised awareness about the Fugitive Slave Law, which contained a number of draconian provisions: it allowed special federal commissioners to cross state lines and arrest anyone of being a fugitive. Judges received financial incentives for ruling in favor of slaveholders. And people assisting fugitives could be fined or imprisoned. The pamphlet, issued by the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society led by Lewis Tappan, sold 13,000 copies within three weeks of its first printing.

Church Debates on the Fugitive Slave Law

“The Bible is Heavier than the Statute Book.”

At Plymouth Church, on Orange between Henry and Hicks, the high profile abolitionist Henry Ward Beecher spoke out against the Fugitive Slave Law. The law allowed federal authorities to cross state lines and kidnap any person of color suspected of being a fugitive.

For white abolitionists kidnapping under the Fugitive Slave Law would always remain in the abstract – a violation that could not be committed against them. But it did not deter pastors with anti-slavery convictions denouncing the law at the pulpit. Brooklyn, the “City of Churches”, so called because of the disproportionate number of churches to people, entered a war of words.

Church Debates on the Fugitive Slave Law

“Is this law right? Is it equitable and just? Does it agree with the law which GOD has given me, when he tells me to love me neighbor as myself?”

At Church of the Pilgrims, Richard S. Storrs asked his congregation to reflect on which law held more weight – religious or secular.

Henry C. Bowen, Lewis Tappan’s son-in-law, founded the church on the corner of Henry and Remsen. Bowen left Church of the Pilgrims to organize Plymouth Church which became a center of abolitionism under Beecher’s leadership.

Church Debates on the Fugitive Slave Law

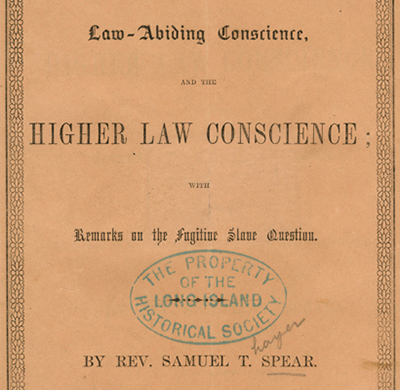

“God’s law is certainly higher than man’s.”

Samuel T. Spear’s South Presbyterian Church, on Clinton and Amity, included parishioners such as the prominent white abolitionist John Rankin. He was as an executive officer in the American Anti-Slavery Society, American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society and president of the Brooklyn Anti-Slavery Society.

Church Debates on the Fugitive Slave Law

“If Law cannot be executed, it is time to write the epitaph of your country!”

Ichabod Spencer preached an entirely different kind of message at Second Presbyterian Church, located at Clinton and Fulton. According to Spencer it was not slavery that was on trial. Rather, the future of the Union and its preservation was at stake.

In response to the Fugitive Slave Law, New Yorkers and Brooklynites formed three vigilance committees. William J Wilson, Junius Morel, and T. Joiner White and others formed a group called the Committee of Thirteen. They offered financial assistance to freedom seekers, protection from slavecatchers and protested colonization. Information is scarce on the other organizations – a Committee of Nine in Brooklyn and Committee of Five in Williamsburg.

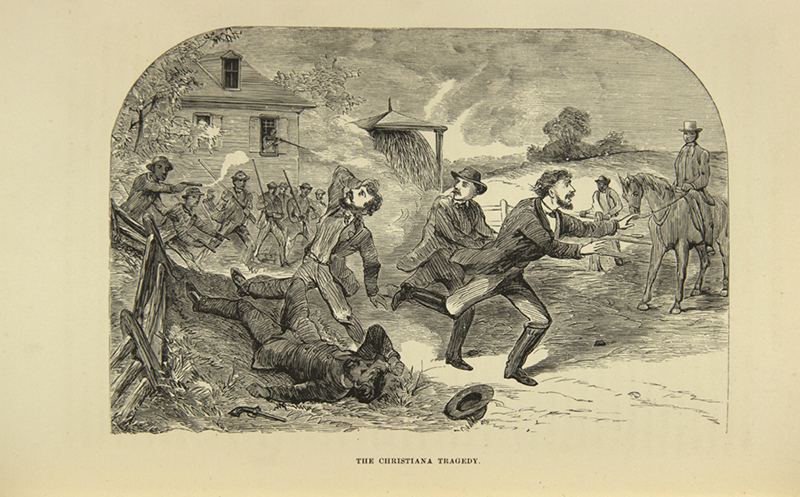

In 1851, all three committees worked together on the high profile Christiana Patriots Case. When fugitives in Christiana, Pennsylvania killed the slave catcher that had come to arrest them, they were charged with treason, riot and murder. Vigilance committees in New York and Brooklyn raised funds for the defendants.

Territorial gains made during the Mexican-American War (1846-1848) reopened debates on the expansion of slavery. A new political party – the Free Soil Party – believed that the westward expansion of slavery should be halted. However, they did not wish to see the deeply rooted institution of slavery dismantled and they did not support the abolitionists, whom they deemed fanatics. Walt Whitman, one of Brooklyn’s most famous residents, was an ardent Free Soiler.

From March 1846 to January 1848, Walt Whitman served as editor of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, the city’s Democratic newspaper. Under his leadership, the newspaper printed highly derogatory passages about both abolitionists and African Americans. One editorial described the abolitionists as “foolish and red-hot fanatics”, with “angry

voices.”

Whitman did not condemn the institution of slavery in the south nor did he support political and legal equality for African Americans. But he did oppose the expansion of slavery in the West. When he expressed support for the Wilmot

Proviso, intended to bar slavery from territories

acquired during the Mexican-American War, he was fired.

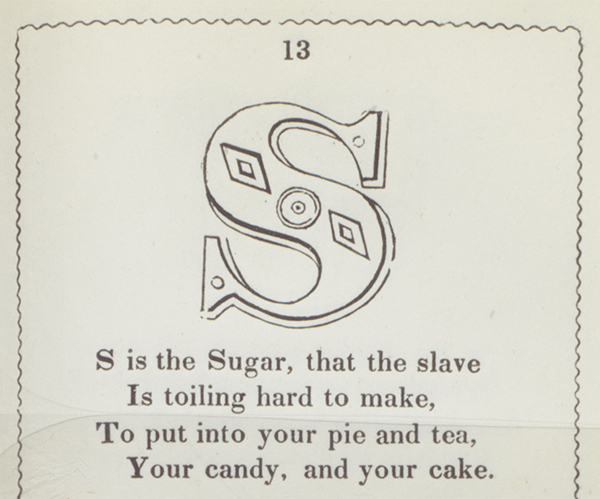

Queen Sugar

Section 4: Lesson 13

As historian Craig Steven Wilder has noted, if “King Cotton” ruled Manhattan’s economy, then “Queen Sugar” reigned supreme in Brooklyn.

The sugar industry, so crucial to Brooklyn’s growth, exploited land and labor from the southern slave plantations of Louisiana to the cane fields of Cuba.

Section 4: Lesson 13

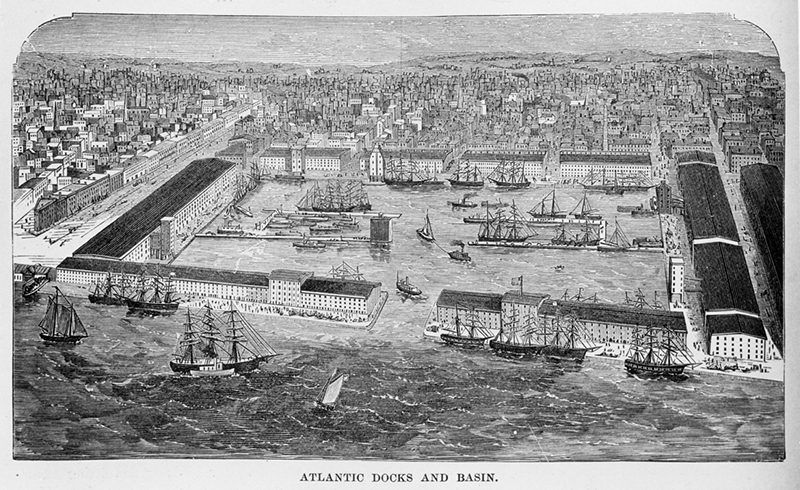

Brooklyn – the “walled city.”

By 1840, Manhattan’s waterfront warehouses had become overcrowded and expensive. Developer Daniel Richards turned his sights to Brooklyn. The result was the Atlantic Docks which transformed Red Hook’s marshland into an industrial wall around Brooklyn. Its success catalyzed further development.

The prosperity of Brooklyn’s newly industrialized waterfront was tied to the economies of slavery. From Williamsburg to Red Hook, the city’s warehouses stored sugar, cotton, and tobacco – all valuable commodities produced by unfree labor.

Section 4: Lesson 13

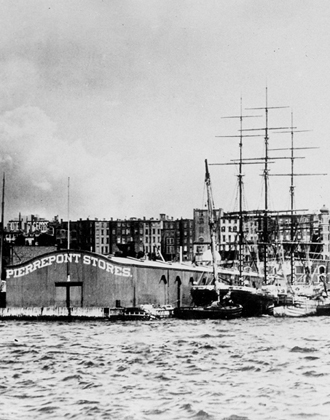

A generation of Brooklyn industrialists, including the Pierrepont and Havemeyer families profited from the nation’s sweet tooth.

William and Henry Pierrepont were the sons of Hezekiah Beers Pierrepont, Brooklyn’s first land developer. In 1857, the brothers opened the Pierrepont Stores (or warehouses) designed to house commodities until the taxes were paid at the Customs House in Manhattan.

The Pierreponts invited companies that traded with Puerto Rico, Cuba, and the South to store their goods at the warehouses. One of the major commodities stored at the Pierrepont warehouses was sugar.

Section 4: Lesson 13

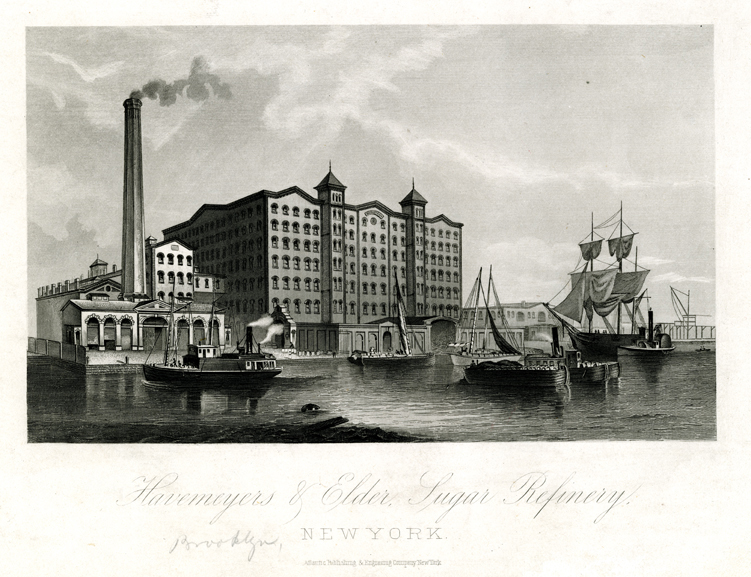

A generation of Brooklyn industrialists, including the Pierrepont and Havemeyer families profited from the nation’s sweet tooth.

In 1807, William Havemeyer, a German immigrant, opened a sugar refining business in Manhattan. Sugar was still a luxury commodity enjoyed by the city’s elite. By 1857, changes in technology allowed sugar to be cheaply produced.

The Havemeyers relocated their business to Williamsburg, where they began to store and refine sugar on site and thereby retain more profit. By the late 19th century, Havemeyer joined with several other magnates to establish the Sugar Refineries Company in Brooklyn. It controlled 98% of the nation’s sugar production. By 1900, the Havemeyer Company was renamed Domino Sugar.

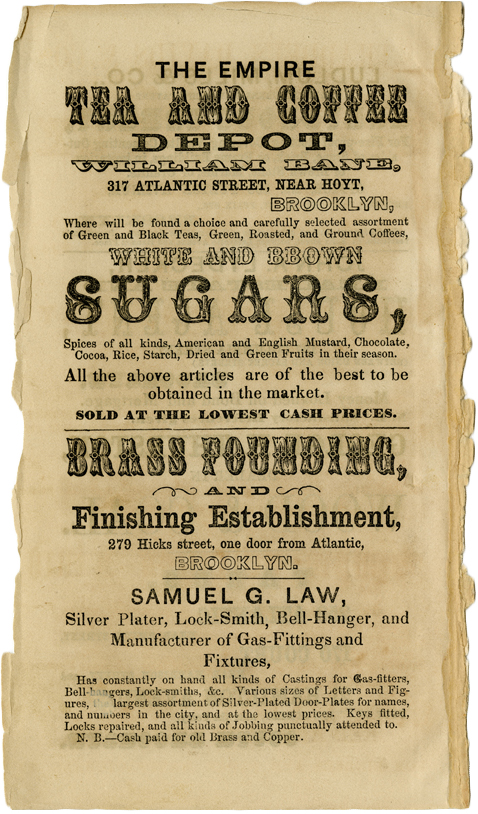

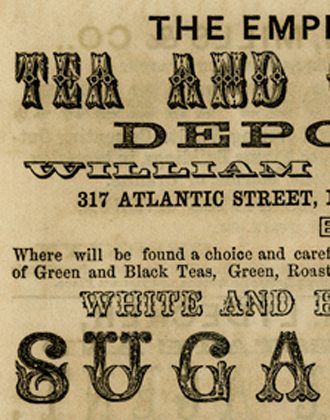

Sugar, spices, coffee, rum and sugar were all coveted consumer products in Brooklyn and beyond. They were prominently advertised in various publications including newspapers and city directories. But all of the notices contain a silence about the product’s source or origins. Many enslaved laborers lost their lives working in oppressive conditions to produce these highly coveted goods.

Section 4: Lesson 13

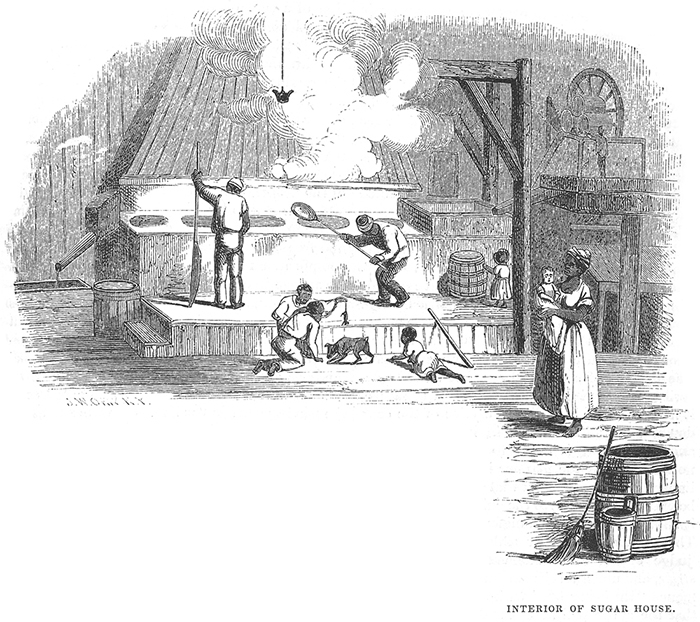

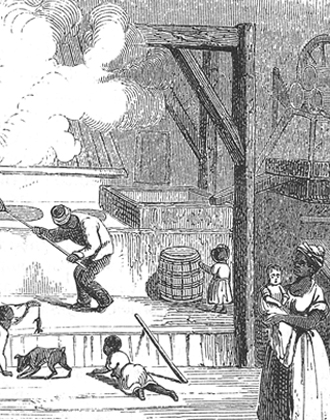

Unfree laborers produced sugar, tobacco and cotton – commodities that guaranteed Brooklyn’s wealth. Many people of African descent lost their lives working in the fields of South Carolina, Louisiana, Cuba and Puerto Rico.

In the case of sugar production, the work was relentless, exhausting, and dangerous. The season began in late December with the prolonged and backbreaking task of planting the sugar crop. By spring and early summer, workers removed weeds from the growing sugar canes. During the summer months, laborer built canals and ditches to ensure the fields had sufficient drainage. By early November, once the crop was in harvest, men, women and children worked non-stop. They cut sugar canes, stripped the leaves, and transported them to the mill for processing. The mill, where workers crystallized the sugar and packed it to destinations like Brooklyn, was oppressively hot. Once the year’s work was complete these laborers rested a few days before crop planting began again. That’s if the worker had not injured him/herself during the grueling work or died from exhaustion. The sugar trade was a death trap for many.

Black Businesses

William J. Wilson, a strong advocate for independence and self-determination in black communities, dedicated his life’s work to Brooklyn.

Wilson was the longest serving educator at the African School in Brooklyn, or Colored School #1, during the antebellum period. Under his tenure, the school expanded and opened a library. He criticized parents of color who sent their children to Brooklyn’s white schools, arguing that black Brooklynites must show solidarity.

But it was his work as a correspondent for the Frederick Douglass’ Paper that gained him national recognition. Under the pseudonym, “Ethiop”, he examined culture, race and politics in columns typified by irreverence, humor, and satire. Wilson urged black Brooklynites to take advantage of the city’s growth and develop independent businesses that reflected their education and capabilities. His wife Mary Wilson owned a small and successful clothing and crockery store, located on Atlantic Avenue.

Section 4: Lesson 14

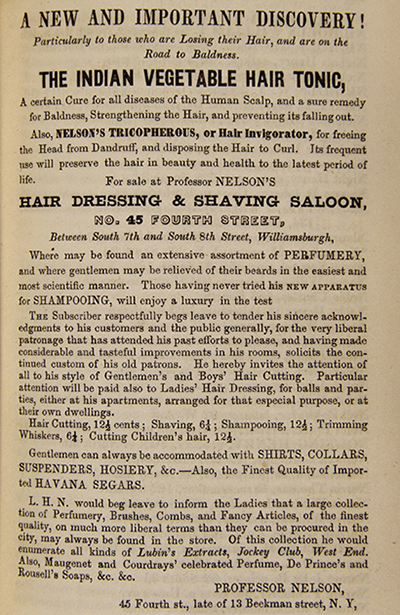

Lewis H. Nelson, a barber and political activist in Williamsburg, was part of a new generation of entrepreneurs, who built their own businesses, creating a context for their own capabilities. Nelson was born in Pennsylvania around 1810. By 1837, he had moved to Manhattan, where he ran a grocery and tea store stocked with “goods free from slave labor.” He moved to Williamsburg around 1841, when Willis Hodges, William Hodges and others began buying land and building a community. Nelson operated a “Hair Dressing & Shaving Saloon” at 45 4th Street which was also his place of residence.

Like many black barbers, Nelson also had a long career as an activist. He served in a benevolent association that supported the education of African Americans and was a founding member of the African School in Williamsburg. He also spoke out publicly against voter discrimination. Nelson died on September 28, 1868, leaving his personal estate to his wife Harriet.

![[Diagram of Freeman Murrow's patented double adjustable paint brush]. Brooklyn Brush Manufacturing Company articles of incorporation. 1978.191. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/096_full_alt.jpg)

Section 4: Lesson 14

Freeman Murrows, another Williamsburg resident, invented an innovative brush for whitewashing, painting and varnishing. Previously brushes had fixed handles so that the entire brush had to be thrown away once the bristles had worn out. The brush was also adjustable and could be angled to make the work easier.

Murrows faced challenges in promoting his invention. He was not permitted to showcase it at the American Institute Fair in 1853 (a precursor to the World Fair), so it was exhibited by a white man instead. The invention won the silver medal. Despite this success, Murrows was unable to secure financing for his business – the Brooklyn Brush Manufacturing Company. In 1855, Lewis Tappan urged his fellows abolitionists to invest in the business at an anti-slavery convention.

Read more...

![[Diagram of Freeman Murrow's patented double adjustable paint brush]. Brooklyn Brush Manufacturing Company articles of incorporation. 1978.191. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/096_crop.jpg)

Freedom Seekers

![[Portrait of Thomas H. Jones]. General Research Division, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/111_full.jpg)

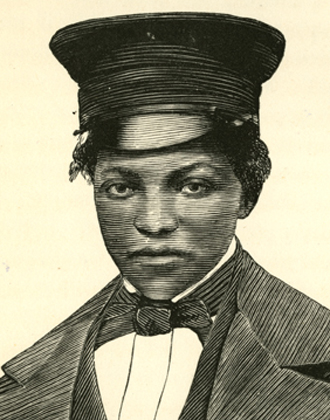

Brooklyn was a “hot bed” of fugitive rescue and activity.

In 1849, Thomas H. Jones, his wife Mary Rynar Moore and their children found refuge in Brooklyn.

Jones was born enslaved on a plantation near Wilmington, North Carolina in 1809. He received financial assistance from a white friend and used the money to emancipate his wife and children. However, North Carolina failed to legalize Moore’s emancipation. To avoid being re-enslaved, she and her children escaped to Brooklyn in 1849. She stayed with Brooklynite Robert H. Cousins, an active member of Brooklyn’s AME Church and an outspoken advocate of voting rights. Jones eventually found the courage to run to freedom too and joined his wife in Brooklyn.

Read more...

![[Portrait of Thomas H. Jones]. General Research Division, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/111_crop.jpg)

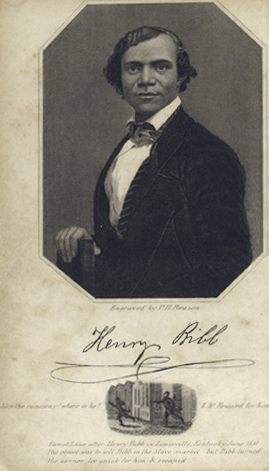

Prominent freedom seekers turned abolitionists such as Henry Bibb spoke in Brooklyn as part of an international lecture circuit.

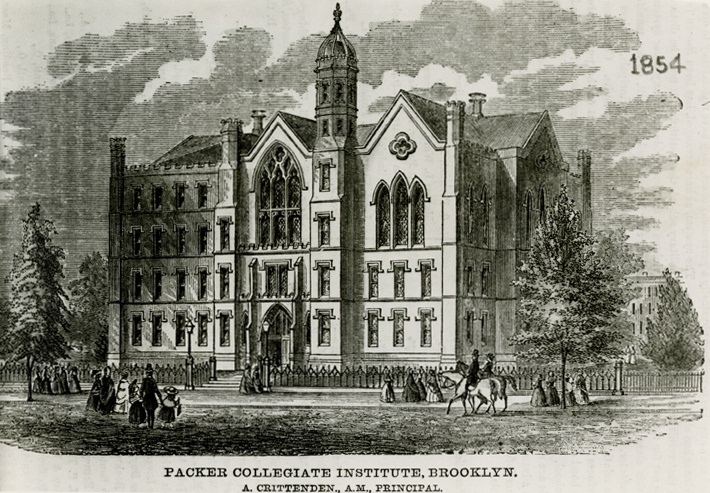

On May 27, 1847, Henry Bibb, a freedom seeker turned abolitionist, spoke at the Brooklyn Female Academy on Joralemon Street (now Packer Collegiate Institute). He returned to Brooklyn two years later and lectured at the Brooklyn AME Church where he raised $2.50 (about $73.60 in today’s money). Brooklyn was a “hotbed” of fugitive rescue, fundraising, and activity.

Henry Bibb, originally a fugitive from Kentucky enjoyed a long successful career as a public speaker and prominent abolitionist.

He published the Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb, An American Slave (1849) designed to tell his own story and provide a source of income as a free man. But former fugitives such as Bibb were often contracted by various anti-slavery societies to tell their story directly to audiences. They challenged proslavery propaganda and revealed the mental, physical, and sexual violence perpetuated upon the black body. Brooklyn was one of Bibb’s many stops on the anti-slavery lecture circuit.

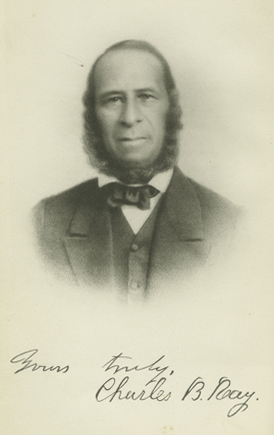

Charles B. Ray was a Manhattan abolitionist who worked closely with colleagues in Brooklyn, particularly in the 1850s on fugitive rescue cases. He collaborated with Lewis Tappan to facilitate the dangerous journey of fourteen-year-old Ann Maria Weems from Maryland to Canada.

Following the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act, African Americans were on high alert. Some free black people outraged by the assault on their civil liberties, emigrate to Canada, Haiti and Liberia. Others risked their lives to help enslaved people find freedom in Brooklyn and beyond. Activity on the Underground Railroad – neither underground nor a railroad, but an informal network of political activists increased significantly.

Section 16: Lesson 16

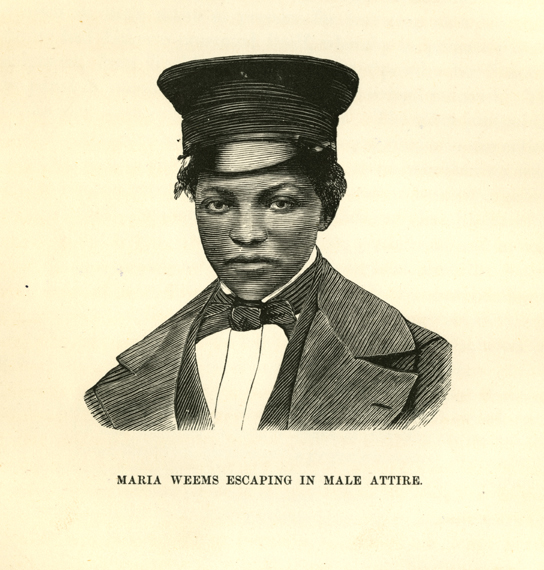

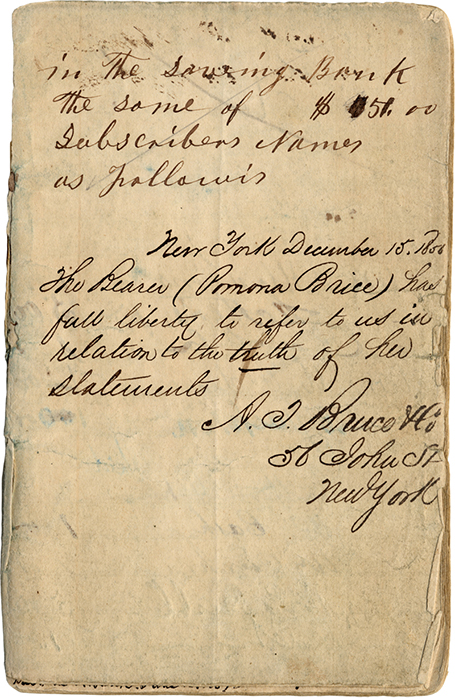

14-year-old Ann Maria Weems represented one of the few cases documenting the passage of a fugitive through Brooklyn.

Weems was the daughter of a free father and enslaved mother. Her parents worked closely with abolitionists to emancipate each member of their family. A Weems Ransom Fund, financed by Quaker abolitionists Henry and Anna Richardson, was established. The Richardsons lived in Britain, so they entrusted control of the fund to their friend Lewis Tappan, a Brooklyn Heights resident, and Charles B. Ray, an abolitionist living in Manhattan.

Read more...

In 1855, after two failed attempts, Ann Maria also succeeded in escaping. She traveled from Washington, DC to Philadelphia and onwards to Brooklyn disguised as a young boy named Joe Wright. She spent two days at Lewis Tappan’s home, where his wife Sarah used $63 from the Weems Ransom Fund to buy Ann Maria new clothes, so she could discard the boys clothing she had used to escape. On November 30, she traveled by train to Canada with Amos Freeman, pastor of Brooklyn’s Siloam Presbyterian Church. When they finally reached Dresden, Ontario, where her aunt lived, Freeman witnessed what he described as a “very affecting” reunion and concluded that Weems had found a “happy home”.

Brooklyn Heights resident, Lewis Tappan, housed Ann Maria Weems at his home before she departed for Canada. Tappan’s wife Sarah used $63 from the Weems Ransom Fund to buy Ann Maria new clothes as she still wore the boys clothing she had escaped in.

Tappan funded many abolitionist activities during the antebellum period and was a white ally in the fight for black civil rights. A businessman from Northampton, Massachusetts, he moved to New York to work with his brother Arthur Tappan. He was spurred to action by a deeply religious evangelical impulse brought about during the Second Great Awakening. He was originally pro- colonization but changed his mind after seeing waves of anti-colonization protests led by African Americans and became committed to abolitionism.

Read more...

The Tappan brothers broke with William Lloyd Garrison, a prominent Boston abolitionist. Garrison believed women should be allowed to serve on the executive committee of the AA-SS. As a result, the Tappans left the AA-SS and formed the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. With Williamsburg resident Simeon Jocelyn and Brooklynite James Pennington, Lewis assisted the Amistad captives during their sensational trial. Lewis prayed at Plymouth Church and Siloam Presbyterian Church, two of the city’s prominent anti-slavery churches.

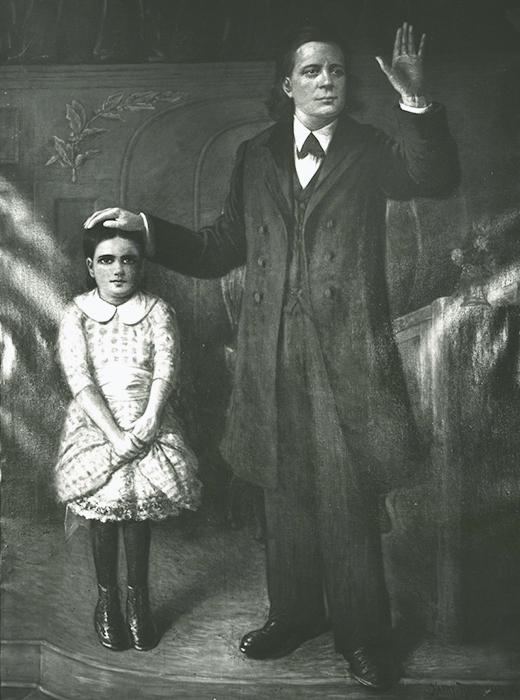

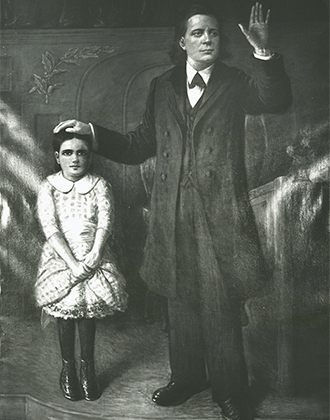

Henry Ward Beecher

In 1847, Henry Ward Beecher left Indianapolis for Brooklyn. For the next four decades the charismatic pastor dominated the city’s politics. He transformed Plymouth Church into a bastion of abolitionist activity during the antebellum decades. The Fulton Ferry was supposedly renamed “Beecher’s Boats” because of the number of people who traveled from New York to Brooklyn on Sunday to hear him speak. During the crisis of Bleeding Kansas as popular sovereignty attempted to settle the problem of slavery’s westward expansion, it is alleged that Beecher sent cases of rifles, also known as, “Beecher’s Bibles.”

Read more...

![[Henry Ward Beecher hate mail]. ca 1860. Plymouth Church of the Pilgrims and Henry Ward Beecher collection. ARC.212: Box 41. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/131_full.jpg)

The general public hated the abolitionists for their radical views. Henry Ward Beecher’s high profile made him a target for much of their wrath. Over the years he received reams of hate mail and death threats.

![[Henry Ward Beecher hate mail]. ca 1860. Plymouth Church of the Pilgrims and Henry Ward Beecher collection. ARC.212: Box 41. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/131_crop.jpg)

![[Ezra Greenleaf Weld, Fugitive Slave Law Convention, Cazenovia, NY] August 22, 1850. Daguerreotype. Courtesy of Madison County Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/123_full.jpg)

In April 1848, some 80 people were arrested on a schooner on the Potomac attempting to flee slavery. Among them were Mary Edmonson, age 16, and her sister, Emily, age 13. The slavetrading company Bruin and Hill of Virginia, wrote to the girls’ parents, demanding $2250 ($64,100 today) for their emancipation. Their father Paul Edmonson, with the help of Washington D.C. abolitionists, approached James W. C. Pennington in New York who recommended Henry Ward Beecher fundraise the money. Using an auction format, Beecher asked the audience to imagine the enslaved girls as their own sisters and daughters. The crowd, appalled at the girls’ experience, donated the money for their emancipation.

Read more...

![[Ezra Greenleaf Weld, Fugitive Slave Law Convention, Cazenovia, NY] August 22, 1850. Daguerreotype. Courtesy of Madison County Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/123_crop.jpg)

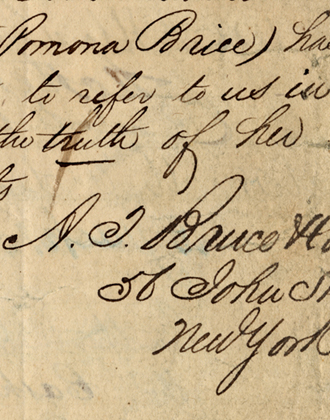

Pomona Brice was originally enslaved in North Carolina. By 1857, she was free and a resident of Brooklyn. Determined to reunite with her family she traveled across the North raising money. She worked with an attorney in Brooklyn and received money from Beecher, Bethel AME Church in Weeksville, and Bridge Street AME Church among others.

It is difficult to say whether her family was ever freed.

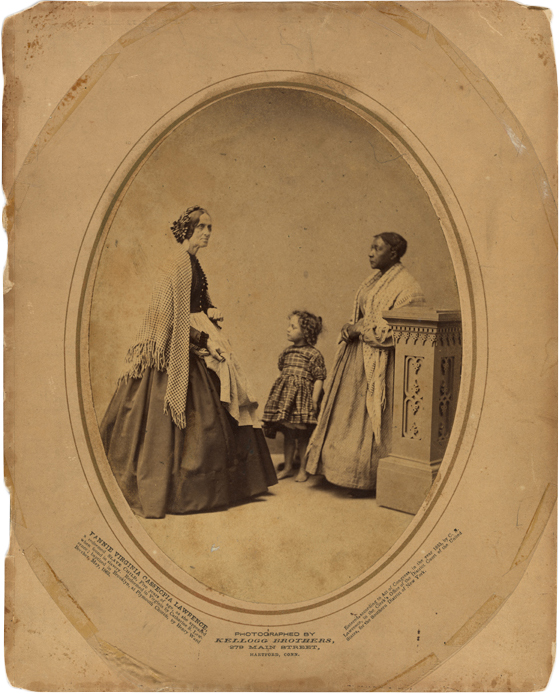

Five-year-old Fanny Virginia Casseopia Lawrence was “fair as a lily”, with a “sweet face, large eyes, [and] light hair.” When Henry Ward Beecher announced to his congregation at Plymouth Church that she had been enslaved they reacted in horror. Rumors circulated that Beecher had found her at a soldier’s hospital in Fairfax, Virginia. In fact, Beecher met Fanny after a parishioner at Plymouth Church had adopted her.

On February 5, 1860, nine-year-old Sally Maria Diggs, nicknamed “Pinky,” was auctioned for $900 at Plymouth Church. She was “nearly white, having only one sixteenth of negro blood.” This was true of many of the women Beecher helped to emancipate, perhaps to appeal to his white audiences. Beecher raised money in auctions, displaying the women and girls to elicit sympathy from his congregation.

Pinky was renamed Rose Ward, after Rose Terry, a parishioner who placed her ring in the collection box for Diggs, and Beecher himself. As a free woman, Diggs attended Howard University and married James Hunt, a lawyer. In 1929, she returned to Plymouth Church for the 80th anniversary of Beecher’s first sermon.

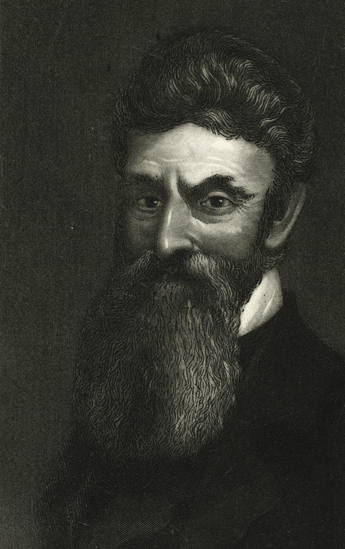

The Gloucesters and John Brown

We consider you a model of true patriotism.”

(Female Brooklyn Residents to John Brown)

“The Lawless & Unchristian Acts of the late John Brown.”

(Congregation at Second Unitarian Church, Brooklyn)

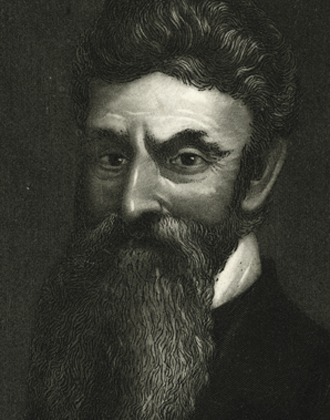

On the night of October 16, 1859, John Brown led 21 men in an attempt to seize the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia with the goal of starting a revolution to end slavery. Not a single enslaved person was liberated. By December 2, John Brown and all of his men were executed. While the raid only lasted for 36 hours, its repercussions were widespread.

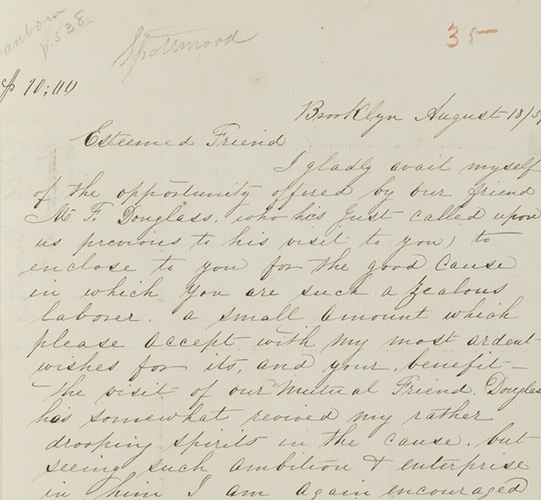

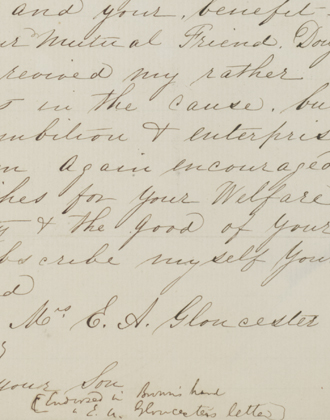

Though the archives might be silent on their contributions, women were at the center of the anti-slavery movement. One of Brooklyn’s most prominent activists was Elizabeth Gloucester.

In August, 1859, Elizabeth Gloucester wrote to John Brown, enclosing $10 in support of his planned raid at Harpers Ferry. The letter also mentions that Frederick Douglass had stayed with the Gloucesters in Brooklyn.

Born free in Viriginia around 1817, young Elizabeth moved to Philadelphia at the age of six. She later married James Gloucester, the son of John Gloucester, founder of black Presbyterianism. The couple moved to New York around 1840, and her husband became the minister of Siloam Presbyterian Church in Brooklyn.

Read more...

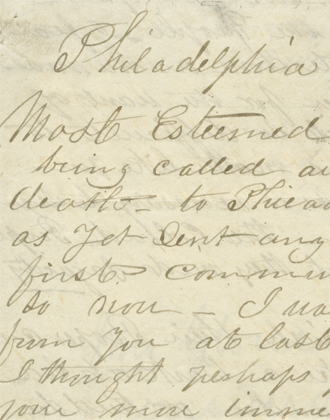

During the antebellum decades, James and Elizabeth Gloucester represented a militant brand of abolitionism. The couple were close friends with Frederick Douglass and wrote to John Brown separately to donate money for his Harpers Ferry Raid.

James Gloucester was the son of John Gloucester, the founder of black Presbyterianism. After moving to Brooklyn he became the pastor of Siloam Presbyterian Church where he continued his anti-slavery activities. The church is located in what is now the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn.

John Brown’s legacy proved too much for Second Unitarian parishioner G. Arthur Leavey. On January 2, 1860, Leavey wrote to church trustees from his new home in Gilmer, Texas. He intended to withdraw his membership from Second Unitarian church (located at the corner of Clinton and Congress) because he could not stand the sermons of its outspoken pastor, Samuel Longfellow, particularly when he “upheld and eulogize[d] the lawless and unchristian acts of the late John Brown.”