1863 ↦

Section 1: Lesson 2

The horses usually rested about five hours a day, while we were at work; thus did the beasts enjoy greater privileges than we did. (John Jea, The Life, History, and Unparalleled Sufferings of John Jea, 1811)

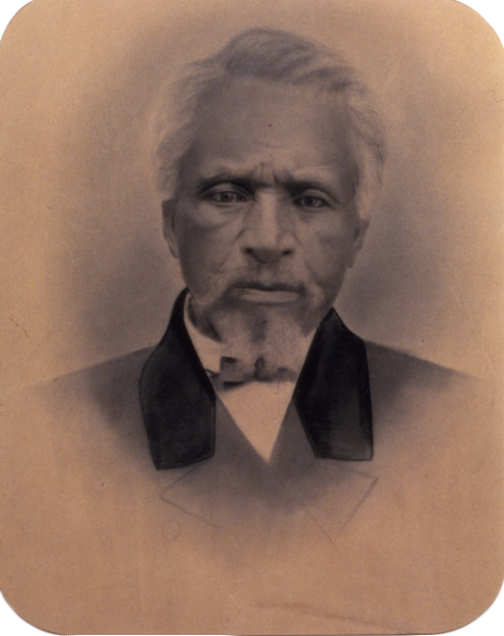

John Jea lived and worked in Flatbush, Kings County during the colonial period and in the early days of the American republic. He was just one of the thousands of enslaved people who fueled the prosperity of Kings County’s agricultural economy.

Jea was born in southern Nigeria in 1773. He was kidnapped at the age of 2½ and sold into slavery. Jea worked on a large farm in Flatbush. His slaveholders, Albert and Anetje Terhune treated him “in a manner almost too shocking to relate.”* The Terhunes forced their enslaved laborers to work eighteen hours a day, seven days a week, with a paucity of food and inadequate clothing. They beat, whipped, and even killed those who complained or could not work.

Despite the physical and psychological torture endured under slavery, Jea seized the opportunity to convert to Christianity and learned to read and write. In 1789, at the age of sixteen, he was manumitted. It is difficult to say exactly why Jea was freed, but occasionally Christian slaveholders faced the moral dilemma of enslaving their fellow Christians. With a new physical and spiritual freedom, Jea traveled as a preacher across the United States, West Indies, and Europe and shared the Gospel and his life story with audiences. He detailed his experiences in the Life, History, and Unparalleled Suffering of John Jea, the African Preacher (1811). His autobiography offers a rare glimpse into the brutality of slavery in Brooklyn from the perspective of an enslaved person.

* Jea states that his slaveholders were Oliver and Anjelika Treibuen in his autobiography. But historian Graham Hodges found no evidence of this couple living in Flatbush at that time. It is possible that Jea created these names to protect himself and others. According to Hodges his actual enslavers were likely to be Albert and Anetje Terhune.

Section 1: Lesson 1

Brooklyn was the slaveholding capital of New York State.

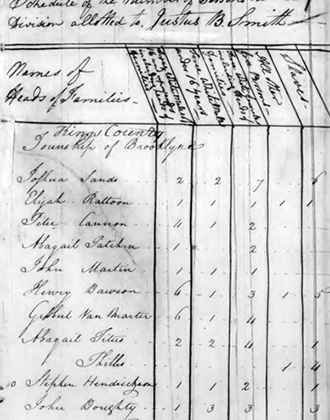

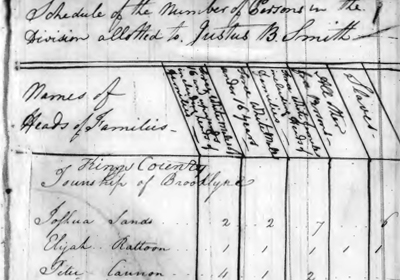

In 1790, the first official federal census revealed that the population of Kings County had doubled in less than a century. 4,495 residents, mostly of Dutch, English, and African descent, lived and worked on the county’s large farms.

Not all were free. In 1738, 25% of Kings County’s residents were held in slavery. In 1790, this number had risen to 30%. On average, 60% of white families were slaveholders; in outer areas, such as the town of Flatbush, this number was as high as 74%. Kings County was a slaveholding capital in New York State.

Slaveholding families that became wealthy during this period included the Lefferts, Lott, Bergen, Vanderveer and Vanderbeek families. Their names are still visible in Brooklyn’s landscape: the Prospect-Lefferts Gardens neighborhood and Lott Street in Flatbush; Bergen Street, which runs East-West from Cobble Hill to East New York; Vanderveer Street in Bushwick; and, Remsen Street (named after a descendant of Ram Jansen Vanderbeek) in Brooklyn Heights. In fact, 82 streets named after Brooklyn’s slaveholding families still exist in the borough today.

Section 1: Lesson 2

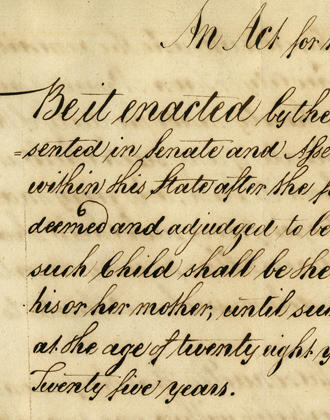

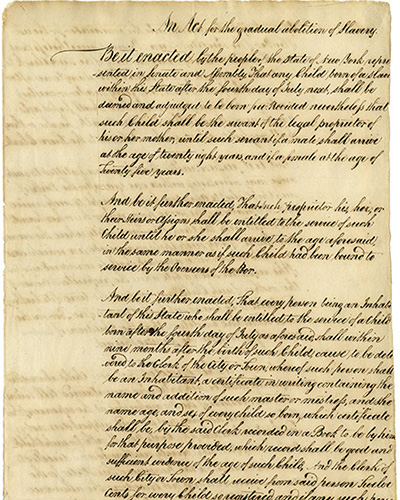

It took twenty-eight years for New York State, and therefore Kings County, to end slavery.

In 1799, New York State made provisions for the gradual emancipation of enslaved people. It was the second to last northern state to do so. After July 4, 1799 children born of enslaved mothers would be free at the age of 28 if male, and 25 if female. Slavery had no end date for people born prior to this date, until 1817, when a further law stipulated that slavery would come to an absolute end on July 4, 1827.

As long as slavery existed so did the desire to be free. During gradual emancipation (1799-1827), anti-slavery activities in Kings County fell into three broad categories:

– the efforts of black people, both enslaved and indentured, to secure their own emancipation through running away, manumission and self-purchase,

– the legal mediation carried by an anti-slavery organization called the New-York Manumission Society,

– a grassroots campaign for equality initiated by Brooklyn’s free black community.

Their work was frequently met with hostility from Brooklyn’s landowners and farmers whose wealth was built on slavery.

![[Cover of Constitution of the Brooklyn African Woolman Benevolent Society] adopted March 16, 1810, published in 1820 by E. Worthington. Negative #85470d. Collection of The New-York Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/019_crop.jpg)

Section 1: Lesson 6

A small, but significant, free black community lived in the areas now known as DUMBO and Vinegar Hill. They pioneered Brooklyn’s anti-slavery movement through grassroots efforts.

In 1810, Brooklynites Peter Croger, Benjamin Croger, and Joseph Smith established the Brooklyn African Woolman Benevolent Society. The mutual aid society’s name referred to noted Quaker anti-slavery activist John Woolman and reflected the organization’s anti-slavery commitment. The Society offered care and financial assistance especially to the widows and children of deceased members.

The Brooklyn African Woolman Benevolent Society frequently worked with Manhattan’s New York African Society for Mutual Relief founded in 1808. Members of both organizations marched together in parades and celebratory processions in Manhattan and Brooklyn. These joint appearances represented a show of political solidarity, the creation of an anti-slavery network that crossed the East River, and the sharing of information and resources.

![[Advertisement for African School]. The Long Island Star. January 18, 1815. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/022_crop.jpg)

Section 1: Lesson 6

The creation of a private African school symbolized literacy as a form of liberation.

In 1815, Peter Croger established a private African school at his home on James Street. The school offered day and evening classes in the “common branches of education.” Croger’s school was vital to the education of black Brooklynites after the district school refused to teach children of color.

Croger’s work symbolized literacy as a form of liberation. Through literacy, they sought to empower people of color to emancipate their minds from the mental oppression of racism. They also challenged the racist perception that people of African descent were not capable or prepared to be equal citizens in the United States.

![[Bridge Street African Methodist Church]. Eugene L. Armbruster. 1923. Eugene L. Armbruster photographs and scrapbooks. V1974.1.1342. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/025_crop.jpg)

Section 1: Lesson 6

Bridge Street AWME Church, Brooklyn’s oldest black church now located in Bedford-Stuyvesant, was founded by grassroots anti-slavery activists as a political base during gradual emancipation.

In 1816, Reverend Richard Allen founded the independent African Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia. Two years later, inspired by anti-racism developments in Philadelphia’s black community, Peter Croger, his brother Benjamin Croger, Israel Jemison, Cesar Springfield, and John E. Jackson founded the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church on High Street in Brooklyn.

The church was established in response to the racism at Brooklyn’s Sands Street Methodist Church. Founded in 1794, it was one of Brooklyn’s oldest churches, and its congregation included people of European descent, African descent and Native Americans. But when African Americans were segregated to an end gallery for which they had to pay and forced to listen to the pro-slavery sermons of its Irish pastor Alexander M’Caine, they renounced their membership.

The Brooklyn AME Church became central to the lives of ordinary people. Not only a place of worship, it served as a venue for educational initiatives, political protests, and temperance meetings. They church also assisted with fugitives or freedom seekers newly arrived in the city.

Section 1: Lesson 6

On July 4, 1827 slavery ended in New York State. Black New Yorkers chose to celebrate the next day in order to avoid reprisals and comment on the paradox of slavery and freedom in the United States.

Crowds gathered along Manhattan’s Broadway to celebrate Emancipation Day on July 5, 1827. James McCune Smith, a prominent abolitionist living in Manhattan, described it as a “real, full-souled, full-voiced shouting for joy … marching through the crowded streets, with feet jubilant to songs of freedom!”

A week later, on July 12, 1827, black led benevolent societies took to the streets of the village of Brooklyn. They formed a “long and handsome procession,” accompanied by banners and several bands.

But emancipation brought tenuous liberties.

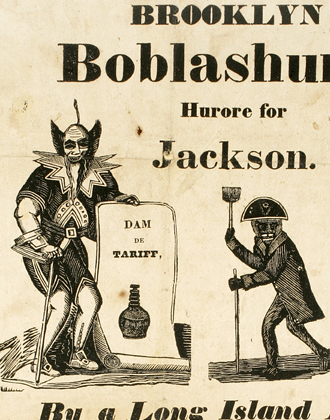

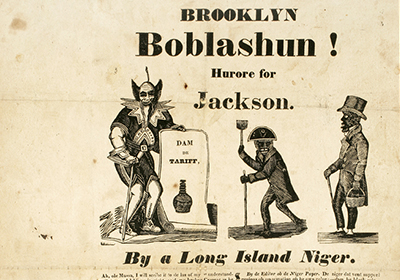

White anxiety in a post-emancipation society often exposed itself through racism and mockery. The Bobalition print series, the name a corruption of “abolition”, reflected these hostilities. The series began in Boston at the turn of the nineteenth century and quickly gained popularity in cities such as Boston, Philadelphia, London and Brooklyn. Christian Brown’s “Brooklyn Boblashun!” shown here, was produced in 1829. Its features are typical: visual caricatures and text that mocks emancipation and belittles the intelligence of African Americans.

During the post emancipation years, black Brooklynites confronted pervasive racial injustice. Inequality in education, housing, voting, and employment was commonplace. Despite their own oppression in “free” New York, communities of color strengthened their commitment to equality through self-determination, self-preservation and protest.

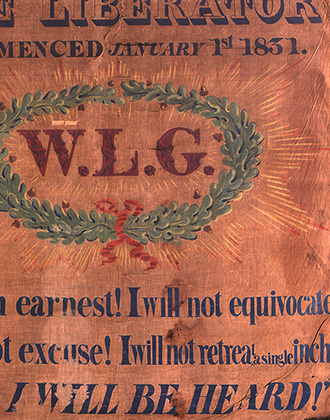

In the 1830s, the abolitionists, a group of humanitarian reformers, burst onto the political scene in the United States.

On December 4, 1833, sixty-two reformers met in Philadelphia to form the American Anti-Slavery Society, establishing their headquarters in Manhattan. Abolitionism resulted from two political impulses – black activism and white evangelical perfection. As a result, the movement attracted men and women, black and white, from different social classes. It was the first time in U.S. history that activists crossed racial and gender lines to work together with mutual purpose.

Abolitionists differed from previous anti-slavery activists in their rejection of gradual emancipation schemes. Instead they called for the immediate end to slavery. They denounced compensation to slaveholders, condemned colonization schemes, criticized institutional ties (both secular and religious) to slavery, and agitated for political and legal equality for African Americans.

The American Anti-Slavery Society’s brand of abolitionism, or immediatism, became closely associated with Bostonian, William Lloyd Garrison. George Hogarth, pastor of the AME Church and an educator at the first public African school in Brooklyn, was an early supporter of the interracial movement and a Garrisonian. He distributed the Liberator, Garrison’s abolitionist newspaper throughout Brooklyn. It featured letters, poems, news, and notices intended to build a national anti-slavery network.

![[Abolition disclaimer]. The Long Island Star. July 14, 1834. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/037_crop.jpg)

Section 2: Lesson 9

Six months after forming the American Anti-Slavery Society, the abolitionist battle against racism and slavery was firmly entrenched in the city of New York.

But the city’s deep economic ties to the South made the situation volatile. In July 1834, the tension erupted. Mobs attacked black and white abolitionist homes and places of worship. They also targeted scores of ordinary black New Yorkers. In the immediate aftermath of these riots, white abolitionists sought to clarify they were radical activists but not anarchists. Two white abolitionists who founded the American Anti-Slavery Society, Arthur Tappan and John Rankin, signed and posted handbills across New York and placed notices in a variety of newspapers including the Long Island Star.

Brooklyn residents were appalled by the violence. Describing the riots as “disgraceful to the character of the city,” the Long Island Star simultaneously indicted Manhattan and praised the emerging city of Brooklyn. By no means a bastion of tolerance and equality, Brooklyn did offer new opportunities for activists wishing to mold the city’s character.

Manhattan’s Anti-Abolition Riot became a turning point in abolitionism in Brooklyn. White abolitionists such as Lewis Tappan, Samuel Cox and Joshua Leavitt eventually left Manhattan and moved to Brooklyn, where they built upon a vibrant anti-slavery movement long established by black Brooklynites.

Section 3: Lesson 11

Established by 1838, Weeksville was one of New York’s earliest and most successful black communities intended as a political base.

Sylvanus Smith was a free black man living in the village of Brooklyn. He was one of the earliest land investors in Weeksville, a free black community that thrived during the antebellum decades.

From Suburb to City

The town of Brooklyn was transformed by land speculation during the early nineteenth century. In 1804, Hezekiah Beers Pierrepont, a pioneering developer purchased a sixty-acre farm in Brooklyn Heights. When his friend, Robert Fulton, developed the steam ferry that reduced commuting times between Brooklyn and Manhattan, the first U.S. suburb was born. By 1817, Pierrepont owned most of Brooklyn Heights and began to parcel it off to individual land investors. In 1834, Brooklyn had outgrown its suburban status and was an independent city.

But the Panic of 1837 brought Brooklyn’s rapid urbanization to an end. Property prices plunged and stayed low as a ten year economic depression followed.

Founding of Weeksville

Just one year following the Panic, free black Brooklynites including Smith intentionally founded the village of Weeksville. In 1821, the New York State Constitution eliminated all property qualification for white men and introduced a $250 property requirement for black men. Weeksville was established, in part, as an answer to this discrimination. Brooklyn’s free black community created a landowning community that would support them as full citizens with voting rights.

Section 4: Lesson 13

Brooklyn – the “walled city.”

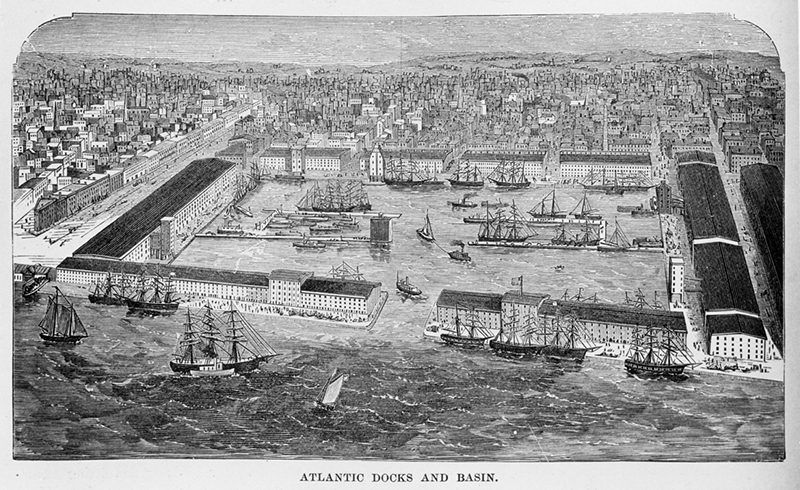

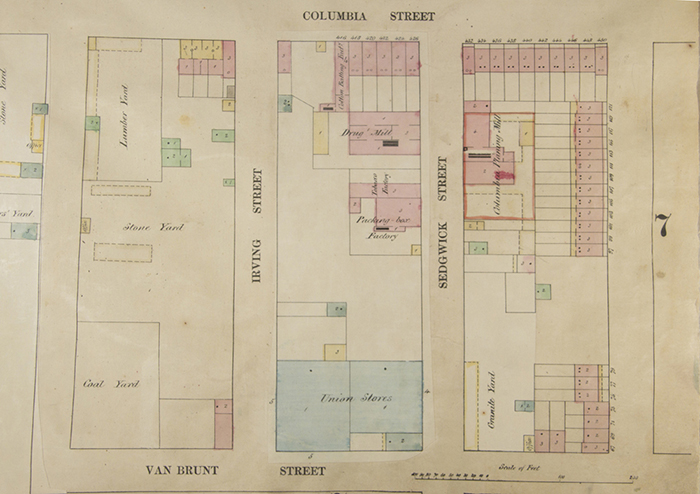

By 1840, Manhattan’s waterfront warehouses had become overcrowded and expensive. Developer Daniel Richards turned his sights to Brooklyn. The result was the Atlantic Docks which transformed Red Hook’s marshland into an industrial wall around Brooklyn. Its success catalyzed further development.

The prosperity of Brooklyn’s newly industrialized waterfront was tied to the economies of slavery. From Williamsburg to Red Hook, the city’s warehouses stored sugar, cotton, and tobacco – all valuable commodities produced by unfree labor.

Section 15: Lesson 15

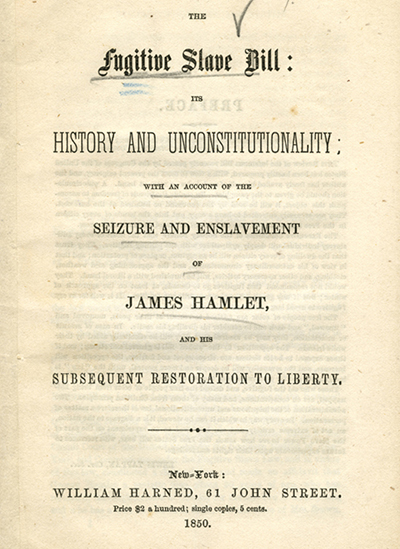

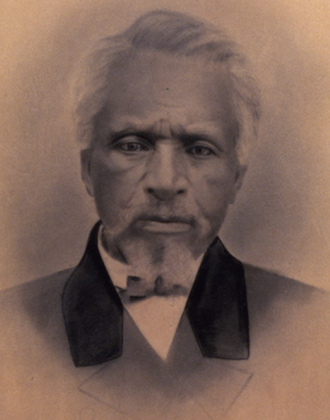

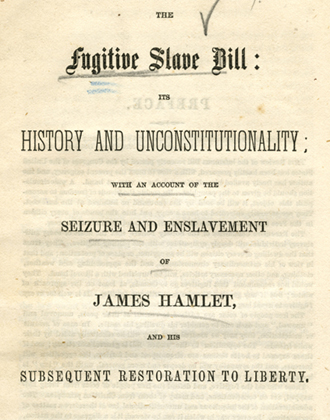

On September 26, 1850, Williamsburg resident James Hamlet, was arrested near his workplace in Manhattan. The arrest was based entirely on his alleged enslaver’s accusation that Hamlet was a fugitive. Under the Fugitive Slave Law, Hamlet was not permitted to testify on his own behalf and he was not entitled to a trial by jury. He was imprisoned and taken to Baltimore.

Hamlet’s arrest outraged abolitionists who quickly fundraised the $800 needed for his release. On October 2, black New Yorkers packed Zion Church in Manahattan – two thirds of attendees were women. Weeksville resident Junius C. Morel and Brooklyn resident Robert H. Cousins were among the speakers and organizers that day. This pamphlet was also part of that fundraising effort, which was ultimately successfully. Approximately 5,000 New Yorkers gathered at Broadway and City Park in Manhattan to celebrate his return. He was reunited with his wife Harriet and three young children, and a final celebration took place at the AME Church in Brooklyn.

The pamphlet also raised awareness about the Fugitive Slave Law, which contained a number of draconian provisions: it allowed special federal commissioners to cross state lines and arrest anyone of being a fugitive. Judges received financial incentives for ruling in favor of slaveholders. And people assisting fugitives could be fined or imprisoned. The pamphlet, issued by the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society led by Lewis Tappan, sold 13,000 copies within three weeks of its first printing.

We consider you a model of true patriotism.”

(Female Brooklyn Residents to John Brown)

“The Lawless & Unchristian Acts of the late John Brown.”

(Congregation at Second Unitarian Church, Brooklyn)

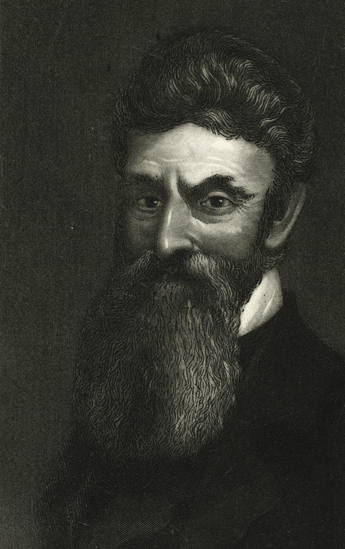

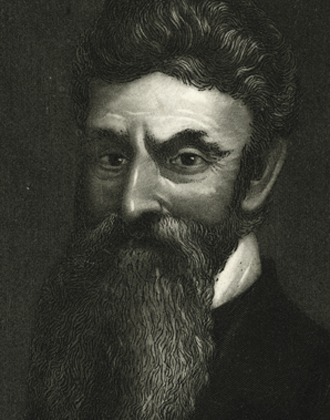

On the night of October 16, 1859, John Brown led 21 men in an attempt to seize the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia with the goal of starting a revolution to end slavery. Not a single enslaved person was liberated. By December 2, John Brown and all of his men were executed. While the raid only lasted for 36 hours, its repercussions were widespread.

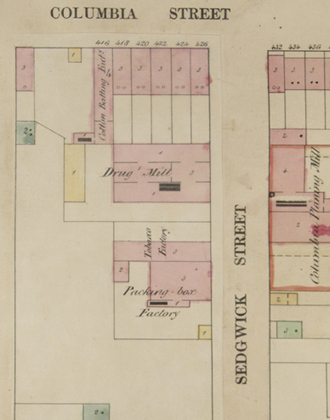

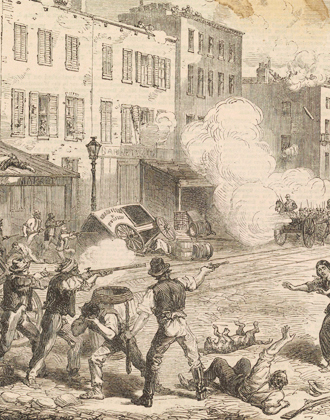

Brooklyn’s Tobacco Factory Riots (1862) were an important and often overlooked precursor to the Manhattan’s Draft Riots (1863).

In August 1862, African American workers, mostly women and children, were assaulted by Irish mobs at the Tobacco Factory on Sedgwick Street in Brooklyn. Even the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, often responsible for some of the most derogatory passages about black Brooklynites during the 19th century, wrote:

We regret most profoundly that, a city, so justly celebrated for its law and order as Brooklyn, should have been so disgraced.

Fear that fugitives and newly emancipated people would move to Brooklyn and take scarce jobs exacerbated hostilities between Irish and African American workers. The Irish, impoverished and marginalized themselves, had emigrated to America to escape the horrors of Ireland’s devastating Potato Famine between 1845 and 1852. But they were greeted with discrimination and limited economic opportunities. Irish immigrants and African Americans competed for the same occupations as laborers, waiters, servants and washerwomen.

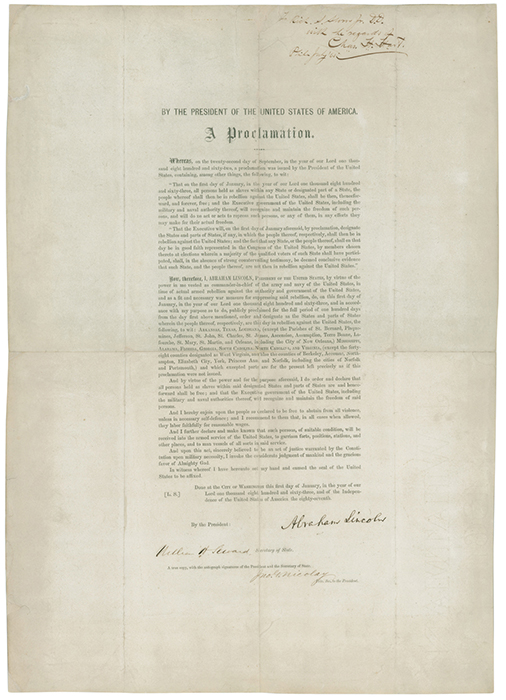

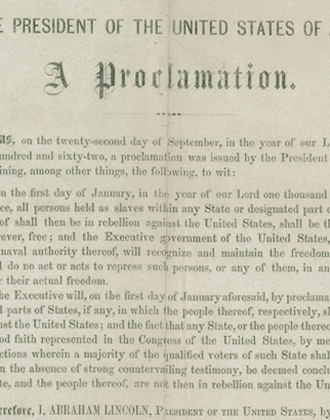

On January 1, 1863, Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation took effect.

All persons held as slaves within any state […] in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.

But the now iconic document did not provide freedom for all. The Emancipation Proclamation did not apply to the approximately 500,000 enslaved people living in the Border States loyal to the Union – or those living in Union occupied confederacy states. Nevertheless, it was critical in making the destruction of slavery a stated goal of the Civil War.

From Monday, July 13 to Thursday, July 16, 1863, mobs of white people, mostly working class Irishmen, tore through Manhattan’s streets. What began as a mass protest against the draft turned into a full-blown riot. Mobs attacked public buildings, businesses, the mayor’s residence, police station, the Armory and the Colored Orphan Asylum. Some of the worst atrocities were committed against black New Yorkers.

New York’s Draft Riots remain the largest and bloodiest urban insurrection in U.S. history.

![[Cover of Constitution of the Brooklyn African Woolman Benevolent Society] adopted March 16, 1810, published in 1820 by E. Worthington. Negative #85470d. Collection of The New-York Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/019_full_alt.jpg)

![[Advertisement for African School]. The Long Island Star. January 18, 1815. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/022_full.jpg)

![[Bridge Street African Methodist Church]. Eugene L. Armbruster. 1923. Eugene L. Armbruster photographs and scrapbooks. V1974.1.1342. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/025_full.jpg)

![[Abolition disclaimer]. The Long Island Star. July 14, 1834. Brooklyn Historical Society.](http://pursuitoffreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/037_full.jpg)